Discussion of taxation in the UK is

bedevilled by two problems: one familiar and one less obvious. The

familiar one is to imagine the level of taxation is separate from the

level of public services and welfare. Most voters and much of the

media understand the two are connected, which is why the Tory attack

on Labour’s ‘tax bombshell’ is so misplaced. A majority want

public services to improve, and know that requires higher taxes [1],

so all the Conservatives are doing is reminding voters that Labour is

more likely of the two parties to improve public services.

Yet this familiar point gets forgotten

when we come to the less familiar problem, which is historical

comparison. It is now well known that UK taxes as a share of GDP, as

measured by the OBR, are currently higher than they have been since

1948 (see

Ed Conway here for example). This sounds bad, until

you remember the first problem, which is that it is pointless to

discuss taxes without also discussing public services and welfare

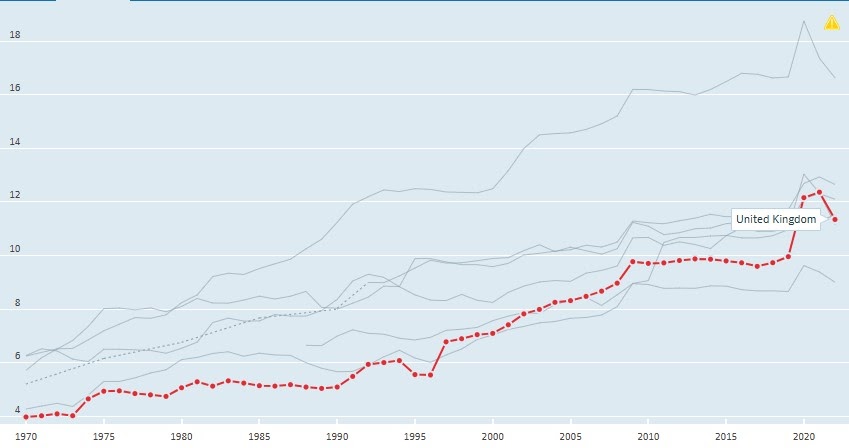

payments. The elephant in the room here is health spending. Below is

OECD

data on total health spending as a share of GDP in

each of the G7 countries, with the UK in red.

Health spending as a share of GDP in

the G7

Health spending as a share of GDP has

been trending upwards in all the major economies since at least 1970,

for familiar reasons like longer life expectancy and advances in what

medicine can do. If health spending is mainly paid for through taxes,

then unless some other large item of government spending is trending

in the opposite direction, taxes are bound to be at historic highs.

For some time in the UK there was such an item, defence spending, but

once that peace dividend ended there has been nothing to take its

place. Of course if health spending is not paid for by taxes citizens

have to pay for it by some other means. The top line in the chart

above is the US, where spending is so high in part because it is a

very inefficient insurance based system.

I have heard journalists in the media

say that UK taxes are at record levels countless times, but I have

never heard them also say: ‘but of course this reflects the steady

increase in health spending as a share of GDP’. The more general

point is that talking about tax without discussing what it pays for

is just uninformative. [2]

International comparisons of taxation

are better, because advanced economies have similar structures to

their public sectors. Here is the same chart as above for total tax

as a share of GDP (source).

Total tax as a share of GDP in the G7

Note the definition used here is a

little different from the national accounts total the OBR uses, so

using this measure UK taxes in 2022 are similar as a share of GDP to

taxes in the early 80s. France has the highest tax share in 2022,

followed by Italy and then Germany. Indeed most major European

countries have a higher tax share than the UK, as Ben

Chu shows here. The UK share is similar to Canada and

Japan, while the US has the lowest tax share. (Will Dunn shows an

international comparison for taxes on wage income here.)

Although more informative than

historical comparisons, looking at other countries has obvious

pitfalls. The US tax share is so low mainly because most US citizens

pay via their employers for health cover through insurance companies.

It doesn’t mean that US citizens are better off because taxes are

low, because their wages are lower so firms can afford to pay for

health insurance. If we ignore the US for this reason, then the UK

has amongst the lowest tax take among the G7, and also the lower than

most major European countries.

While international comparisons of

taxes are better than looking at historical trends, they are not

ideal because – as the US shows – the structures of the public

sectors are not identical. Partly for this reason, the OECD compiles

an analysis of total public and private spending on what it calls

“social expenditure”, which is mainly health and welfare. I

discussed this data in

this post. However, even if we restrict ourselves to

total public spending on social expenditure, the OECD

estimates that the UK has the lowest spending in the

G7 (at 22% of GDP), even just below the US (at 23%). France tops the

table at 32%, followed by Italy (30%), Germany (27%) with Japan and

Canada both on 25%.

This suggests that public spending in

the UK is unusually low compared to other major countries, and as a

result taxes are unusually low. This should come as no surprise,

because public spending excluding health has been cut back sharply

since 2010, as this

chart from the Resolution Foundation shows.

What international comparisons tell us

is that these cuts in public spending have moved the UK to the bottom

of the G7 in terms of spending and taxation. UK public services are

in crisis not because they are unusually inefficient, but simply

because the Conservative government has chosen to spend far too

little on them in order to get taxes unusually low compared to other

G7 and major European countries. The Conservatives are going to lose

this election badly in part because they continue to prioritise tax

cuts over improving public services.

Which means UK taxes are too low, and a

Labour government is going to have to raise taxes to meet both its

pledges and expectations about public spending. (The National

Institute comes to similar conclusions here.)

The question Rachel Reeves and the Treasury will have to answer is

whether

they can raise enough using the taxes left after you exclude those

they have promised to keep at existing planned levels?

If not, will they break these election pledges, or will the public

sector remain underfunded and the UK remain under taxed?

Even if Labour can raise enough taxes

without breaking its election pledges to get public spending to

levels similar to other European countries, this may pose

macroeconomic issues. Higher public spending matched by higher taxes

on companies or the better off may end up increasing aggregate

demand, because higher taxes will not be matched by lower private

spending. Together with higher public investment, this will put

upward pressure on interest rates. [3]

However this will be a price worth

paying, in part because public spending at close to current levels is

having a negative impact on economic performance. In particular ever

growing NHS waiting lists are restricting labour supply

and therefore UK output and incomes. If the Labour government is to

be successful in ending a period of very weak growth in living

standards, one of the things it will have to do is increase levels of

public spending and taxes closer to other major

European countries.

[1] To preempt the tweets from MMTers,

even if you believe that the level of taxes is just what is required

to keep inflation constant, that in turn will depend on the impact of

the public sector on overall demand. For this to be roughly neutral

over the medium term, what the public sector adds to demand with

higher spending it needs to roughly subtract from demand with higher

taxes, so spending and taxes will across countries and over time tend

to move together.

[2] Discussing the composition of total

tax, and how it has changed over time, is more interesting. The

Resolution Foundation has an excellent account here.

[3] Whether this means higher interest

rates, or just rates coming down more slowly than they otherwise

would have done, will of course depend on other influences on

aggregate demand.