Rachel Reeves in her

conference speech (text version) only mentioned the word ‘iron’

twice (‘iron discipline’ and ‘iron-clad fiscal rules’) but

that and the nature of her speech was enough for the headline writers

to label her as a potential Iron Chancellor. Which, I suspect, is

exactly the way she and her team would have wanted it.

Thanks to the

combination of a Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the right wing

press with its influence on the mainstream media [1] the last Labour

government ended with a reputation for being loose with the nation’s

finances. That reputation is completely undeserved, as I have shown

many times, but it is impressions that matter here. In contrast,

because of austerity, the Conservatives get far too easy a ride. It

is the Conservatives who have treated fiscal rules as something you

change every other budget to suit the numbers or politics, yet it is

Labour who have to say their fiscal rules will be iron-clad.

The reality is that

the fiscal rules Reeves is proposing are almost exactly the same as

adopted by John McDonnell when he was shadow Chancellor. Let me

repeat that. The reality is that the fiscal rules Reeves is proposing

are almost exactly the same as adopted by John McDonnell when he was

shadow Chancellor. The big difference between the two shadow

Chancellors is that McDonnell announced higher spending and taxes

that satisfied those rules (in 2017 at least), but Reeves has been

more cautious, so far. In addition, Reeves with Starmer’s support

has exerted more discipline on other shadow ministers over what they

commit to.

At the centre of

these fiscal rules is the golden rule: aiming to match current

spending with taxes. However no Chancellor would be foolish enough to

try and do that year to year. Best practice for a government like the

UK is to have a rolling five year ahead target. I talked about why

the golden rule is a good fiscal rule recently here.

That rule is fine as

long as the economy is doing OK. The catastrophic mistake George

Osborne made was to try and follow it when the economy was just

starting its recovery from the GFC recession. [2] Since then, fiscal

rules have often had clauses of various kinds to deal with that

situation. Labour’s proposed rules do that too, by saying that in a

crisis or the recovery from it fiscal policy would be used to support

the economy rather than meeting the golden rule. Whereas McDonnell

suggested that the Bank define when that was necessary, Reeves has

the OBR doing that job. So Labour’s fiscal rules will not repeat

the disaster of 2010 austerity.

Crisis apart, the

golden rule implies using borrowing to invest, and again Reeves has

been very clear that this is what Labour will do. However, like

McDonnell’s fiscal credibility rule, Reeves also has the commitment

to reduce government debt as a share of GDP, probably as a rolling

five years ahead objective. This was included by McDonnell’s team

in their fiscal credibility rule against my advice, because it was

thought to be politically necessary to do so.

As regular readers

will know, my negative view on targeting debt to GDP (or any stock

measure for that matter) has not changed since I

wrote this with Jonathan Portes. That successive

Shadow Chancellors feel the need to include a poor target because

otherwise they would get a lot of flak from the media tells you all

you need to know about the lack of economic expertise in our media. That

expertise says that government debt is not a bad thing, sometimes it

is good to let it increase, and we have no reason to believe that

current levels of debt are in any way harmful or risky. To suggest

that a government that follows the golden rule would be irresponsible

if it failed to reduce its share of debt in GDP is just economic

illiteracy.

Hopefully this

particular target will disappear once Labour are elected. It probably

needs to because the amount of additional public investment

that is needed after years of underinvestment is immense, and it

would be a crying shame if this didn’t happen because of a daft

fiscal rule. Because public investment encourages growth it helps

reduce debt to GDP in the longer term, so cutting back on such

investment because it would in the short term raise debt to GDP is

classic short-termism.

Turning back to

current spending, it is clear that the next government, whatever its

colour, will have to raise taxes and spending once they are in power.

As Sam

Freedman says here “Starmer’s holding position

that he wishes to run “a reforming state, not a cheque-book state”

is transparent nonsense”. As I suggested

here, the only issue is whether a Labour government

does the politically smart thing and acts boldly to increase a

variety of taxes in its first budget, or whether tax increases are

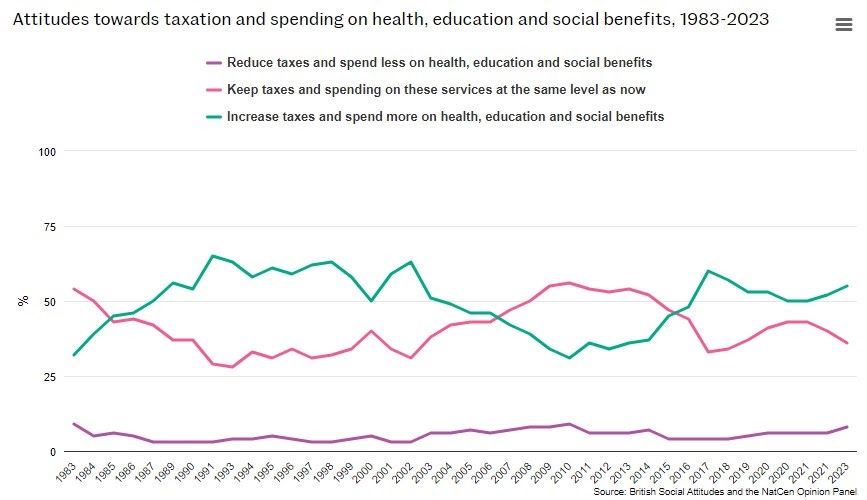

reluctantly spread out over its first term. The public’s desire for

more tax and spend is clear from the latest British Social Attitudes

survey, although not quite as strong as it was in the nineties.

Reeves’s line that

money for additional spending will come from growth is also at best a

holding position. Spending on the NHS, social care, education and so

on as a share of GDP needs to rise, which means higher taxes

as a share of GDP. Once again, those who criticise these fictions of

reform or spending through growth really should focus their attention

on a media that makes such fictions a sensible political strategy for

a Labour opposition that wants power.

Will Labour be

constrained by the macroeconomic situation it finds itself in? We can

consider two possibilities, even though reality will probably be

somewhere between the two. The first is that inflationary pressure

and high (by recent standards) interest rates continue. As long as

Labour follow the golden rule, any extra current government spending

should not be too inflationary because they are funded by permanent

increases in taxes. [3] The shift from private sector to public

sector spending will happen through higher taxes.

The same is not true

for additional public investment, however. In this case the shift

from consumption to investment will come through higher than

otherwise interest rates. However the impact on interest rates is

likely to be small, as public investment can increase substantially

in proportionate terms without rising very much as a share of GDP.

Perhaps more of a concern will be getting the resources for the

projects (e.g. construction workers).

The second

possibility at the other extreme is that UK inflationary pressure

disappears very quickly, as the lagged effects of recent rises in

interest rates begin to be felt. At worst, the UK may be in recession

when the general election is finally called, and by the time Labour

takes power interest rates could be back to their lower bound. In

some ways this reduces Labour’s problems, because they can in the

short run use increases in public investment and current spending

to boost the economy. However, one big advantage of rolling five

year ahead targets is that the recession will be forecast to be over

in five years, so the tax implications of permanently higher current

government spending cannot be avoided.

One final point that

Reeves’s speech brought home was that Labour will be fighting the

2024 election not just its traditional ground of public services but

also on the economy. To Reeves’s credit, she has been persistent at

putting better growth at the centre of her message. While I agreed

with that, if only because the Conservative’s record has been so

poor, many others thought otherwise, because of the structural

reasons why the Conservatives tend to perform better in polls about

‘the economy’. Reeves was correct, and not just because of Truss:

Labour were

level with the Conservatives on the economy six months

earlier. What the Truss disaster ensures is that even if growth picks

up next year, the Conservatives are unlikely to get much credit for

it. [4]

[1] Also to some

extent due to the failure of Labour to counteract this message, in

part because they had an extended leadership campaign.

[2] The centrepiece

of Osborne’s fiscal rules was also a 5 year rolling target for the

current deficit. That rule was adopted because it was suggested by

the IFS, who Osborne’s advisor Rupert Harrison had worked for.

Unfortunately the IFS do not do macro, so their thinking ignored the

problem of recessions where interest rates hit their lower bound.

[3] In theory a

permanent increase in taxes should lead to an equal decline in

consumption. There are two reasons why there might nevertheless be a

positive impact on GDP. First, consumers may not regard the tax increases as

permanent. Second, private consumption tends to be more import

intensive than government spending.

[4] Before the 1997

election, the economy had been recovering well for a few years, but

it wasn’t enough to help the Conservatives, in part because the

forced exit from the ERM had blown their reputation for economic

competence.