Two weeks ago I

described how the UK’s inflation problem has now

become about labour market strength and private sector wage

inflation. Earnings

data released last week has confirmed that view, in

part because of the latest data but also because of revisions to the

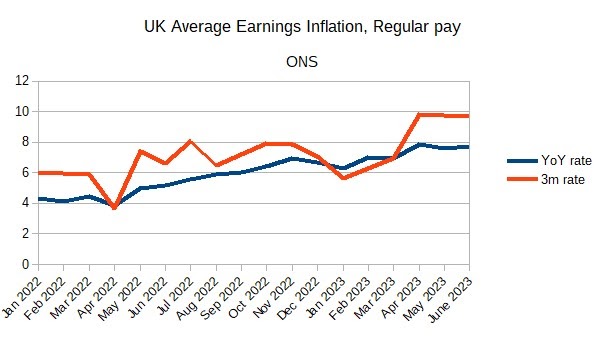

previous two months. Here is both year on year wage inflation, and

the annualised three month rate.

Year on year wage

inflation is at around 8%, and more recent increases have been above

that. If that continues it is consistent with 6-7% inflation, which

is well above the government’s target of 2%. So private sector wage

inflation has to come down. Maybe wage inflation will follow price

inflation down, or perhaps further efforts to reduce aggregate demand

and therefore the demand for labour are needed. That question is not

the subject of this post. Instead I discuss why some on the left find

this diagnosis for our current (not past) inflation problem

difficult.

A year or so ago,

when inflation in the UK was primarily due to higher energy and then

food prices, mainstream economists could legitimately be divided on

what the policy response should be. On the one hand, decreasing

aggregate demand in the UK was not going to have any effect on the

drivers of inflation. On the other hand, it could be argued that

policy should become restrictive to prevent higher inflation becoming

embodied in expectations, because if that happened then inflation

would remain too high after the energy and price shocks had gone

away. To use some jargon, opinions will differ on what the policy

response to supply shocks should be. Until the beginning of 2022

central banks went with the first argument, and did not raise

interest rates. When nominal wage inflation started rising, and it became clear the labour market was tight, interest rates started to rise.

Now mainstream

economists, at least in the UK, are on clearer ground. Excess demand

in the labour market is pushing up wage inflation, and therefore

aggregate demand needs to be reduced to bring private sector wage inflation down.

There may also be excess demand in the goods market, pushing up

profit margins, but the remedy would be the same. (Data on profits is

less up to date than earnings, but as yet there is no

clear evidence that the share of profits has risen in

the UK.) Excess demand in either market needs to be eliminated, which

requires policy to reduce aggregate demand, leading to fewer

vacancies and almost certainly increased unemployment.

The understandable

difficulty that many have with this diagnosis is that real wages have

fallen substantially over the last two years, and nominal wage

inflation is only just catching up with price inflation, so how can

wages be the problem? I have addressed this many times, but let me

try again in a slightly different way.

Inflation over the

last two years has been about winners and losers. The winners have

been energy and food producers, who have seen prices rise

substantially without (in the case of energy at least) any increase

in costs. To the extent that the government can (and is willing),

profits from energy producers can be taxed and the proceeds returned

to consumers through subsidies. But the reality is that much of these

higher profits on energy and food production are received overseas,

and there is nothing the UK government can do about them. As this is

essentially a zero sum game, those who have benefited have to be

matched by those who have lost. The only issue becomes how those

losses are distributed between UK consumers, the profits of other UK

firms, the government and its employees.

Workers in this situation could try and raise nominal wage inflation to

moderate this loss in real wages, and that is one interpretation of

what has been happening. Yet if those in the private sector are

successful in this, who are the losers? They can only be firms,

through lower profits. Why should firms reduce their profit margins

when wages are rising across the board? In a weak goods market they

might be prepared to do so, but there are no signs of that in the UK.

So firms are likely to match higher wage inflation with higher price

inflation. That is the major reason why the price of UK services has

been increasing steadily over the last two years (now at 7.4%).

The key point is

that UK real wages didn’t fall over the last two years because the

profits of most UK firms rose. They fell because the profits of

mainly overseas energy and food producers increased. Trying to shift

this real wage cut onto the profits of other UK firms will not work,

and instead just generates inflation. It is also why nominal wage

inflation, not real wage inflation, is the crucial variable here. We

could debate whether it would be a good idea to see real wages

recover at the cost of falling profits, but it hasn’t happened so

far and is unlikely to happen in the future unless excess demand is

replaced by excess supply.

Those on the left

who find it uncomfortable to hear that nominal wages are growing too

rapidly need to remember that since at least WWII sustained real wage

growth, or the absence of growth, in the UK has not come from lower

profits, but instead comes mainly from productivity growth, with

occasional contributions from commodity price movements and shifts in

the exchange rate. The reason

UK real wages have hardly increased over the last 15 odd years

is because productivity growth has been very weak, energy and food

prices have risen and sterling has seen two large depreciations. [1]

The interests of workers are served by policies that help real wage

growth, and not by seeing nominal wage growth well beyond what is

consistent with low and stable inflation.

If high inflation is caused by excess demand then policy needs to decrease aggregate

demand, which will reduce the demand for goods produced by most firms

leading in turn to a reduced demand for labour. That almost certainly

means unemployment rises. If you worry that the costs of additional

unemployment is too high, then something like a Job Guarantee scheme

makes a lot of sense, although the potential

costs of such a scheme also need to be recognised. Such a scheme does not change the logic, however, that inflation that

is caused by excess demand needs to be corrected by decreasing aggregate demand.

Is there an

alternative to using weaker aggregate demand to bring down inflation?

If wage inflation is too high, it is because firms are having to

grant large nominal wage increases in order to get and keep workers.

To avoid the symptom (high inflation) you need to remove its cause (a

tight labour market), which means either increasing the supply of

workers or reducing the demand for workers by firms. Because the

former is not easy to do quickly (e.g. because of controls on

immigration) then the latter requires a reduction in aggregate

demand.

In the 60s and 70s,

before oil price hikes made a bad situation worse, UK politicians and

some economists were unwilling to see unemployment rise enough to

stop inflation rising. Instead they tried to use price and wage

controls to keep both inflation and unemployment low. This failed,

and UK inflation rose from around 2% in the early 60s to 8% in the

early 70s, before oil prices rose fourfold. The reason is

obvious given the logic in the previous paragraph. If demand is

sufficiently strong (and therefore unemployment sufficiently low)

that firms want to grant nominal wages increases that are

inconsistent with low inflation to attract more workers, then

controls on prices and wages have to persist to stop inflation

rising. But permanent aggregate controls stop productive firms

attracting workers from unproductive firms, which damages long run

real wage growth. Inevitably governments come under pressure to relax

aggregate wage and price controls, and therefore all controls do is

postpone the rise in inflation.

Judging by comments

on past posts, the reaction of some on the left to all this is to

deny the economics, by claiming for example that the Phillips curve

doesn’t exist. This also happened a lot in the UK of the 60s and

70s. The Phillips curve may be hard to estimate (because of the importance of expectations), and may not be

stable for long periods, but the core idea that unemployment and wage

inflation are, other things being equal, likely to be inversely

related at any point in time is sound, as has been shown time and

time again since Phillip’s first regressions.

Evidence should

always trump political preferences in economics. Occasionally I’m

called a ‘left-leaning’ economist, but this is partly because on major

issues since I started this blog economic evidence has pointed in a

leftward direction e.g. austerity and Brexit were terrible ideas.

Neither of those examples has anything to do with political values

beyond the trivial [2]. Facts, at least since I have been writing

this blog, tend to have a left wing bias.

Inevitably, things

are very different for many outside economics (and a few academic

economists as well). The discussions I find hardest following my

posts are those with people whose politics do determine,

intentionally or not, their economic views. Those exchanges are hard

because however much economics I try and throw in, it’s never going

to be decisive because it will not change their political

views. In addition, if I’m arguing with them, their natural

presumption may be that disagreement must arise because my politics

is different from theirs, or worse still that the economic arguments

I’m putting forward are made in bad faith because of hidden

political motives.

To those who do this

the best reply was

given by Bertrand Russell in 1959:

“When you are

studying any matter … ask yourself only what are the facts, and

what is the truth that the facts bear out. Never let yourself be

diverted either by what you wish to believe, or by what you think

would have beneficent social effects if it were believed.”

[1] Brexit is

responsible for one of those depreciations, and it has also lowered

UK productivity growth.

[2[ By trivial, I

mean that reducing most people’s real incomes by large amounts for

no obvious gain is a bad idea.