It is now well established that Rishi

Sunak as Chancellor played a significant role in increasing the death

toll from the pandemic on at least two occasions. The first was to

introduce ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ in the summer of 2020, and the

second was to

advise Prime Minister Johnson to ignore the medical

advice from SAGE to impose a lockdown in the early Autumn and subsequently.

In both cases he will argue that, as

Chancellor, his role was to protect the economy. Yet he did no such

thing. As Chancellor, he failed to understand that to protect the

economy you had to control the virus, which means keeping the number

of people infected low. I and other economists argued

this at the time, but in this post I want to set out

the logic in a new way to show why there never was a health/economy

trade-off.

A decade before the pandemic a

group of us published an article on the economic

effects of a pandemic. One of the main findings of the paper was that

a severe pandemic can involve serious economic costs because

consumers will avoid what we called ‘social consumption’. Social

consumption involves anything that brings consumers into contact with

others, so includes eating out, going to pubs or the cinema, using

public transport etc. Social consumption involves a third of total

consumption, so if people significantly reduce their participation in

these activities the impact on the economy will be large [1].

We could call this effect an

‘unofficial lockdown’. Individuals stay at home rather than eat

out or go to the cinema because they want to avoid catching the

virus, not because they have been told to by the government. The key

point is that if the government does nothing, individual actions

attempting to avoid catching a potentially deadly virus will lead to

a substantial economic slowdown. Swedish GDP fell by 7.6% in 2020Q2,

even though no official lockdown was imposed.

This is why reducing the number of

people infected also helps the economy recover. There is no

health/economy trade-off in this kind of pandemic. If economic policy

encourages people to put themselves at greater risk of getting

infected, as Eat Out to Help Out (EOTHO) did, then any boost to the

economy would have been limited to when the scheme operated, and

thereafter there would only be economic damage as infections

increased. The only situation where this might not happen is if R

(the average number of people infected by one person) was

sufficiently less than one and it remained below one despite EOTHO,

but we know this wasn’t the case and Sunak made a point of not

asking SAGE about it.

While EOTHO played some part in the

second wave that grew during the Autumn of 2020, just as serious a

failure was Sunak arguing against the SAGE proposal for a second

lockdown in September. It is the case that an official lockdown has a

bigger immediate negative impact on the economy than an unofficial

lockdown. This is because, for example, in an unofficial lockdown

-

Many people will not be well

informed, and will not reduce their social consumption much if at

all -

Some people will be well

informed, but decide the risk to themselves is small so they will

not reduce their social consumption, and discount the risk of them

infecting the more vulnerable. -

Employers may force workers to

continue to travel work, even though both the work environment and

travelling to it may risk infection.

Yet for the same reasons, an unofficial

lockdown has less of an effect in reducing R than an official one.

[2] This is what the UK experienced in the Autumn of 2020, even with

the addition of some regionally based restrictions imposed by the

government. With R>1, not only are more people being infected,

with some dying or getting Long Covid, but the economic damage

persists as individuals try to protect themselves by withdrawing

from social consumption.

The UK and other countries experience

of full official lockdowns is that they reduce R to less than one, so

with a short lag infections start falling. This was the case for the

lockdown at the end of March, the one month lockdown in November and

the lockdown in January 2021. Because R<1, the number of

infections fall and then the economic damage caused by individuals

avoiding social consumption dissipates.

My focus on what happens to R is

crucial, because there is a world of difference between R<1 and

R>1. In the former the pandemic is being controlled, so that when

lockdown ends the situation is manageable, and the hit to the economy

from reduced social consumption will be relatively small. If R>1

the damage to the economy just keeps getting larger.

So while an official lockdown might do

more damage to the economy than an unofficial one while it lasts, the

official one deals with the problem, so reduces the time that Covid

damages the economy. In contrast doing nothing, or taking measures

that fall short of a full lockdown, allows infection numbers to

increase and so allows damage to the economy to persist.

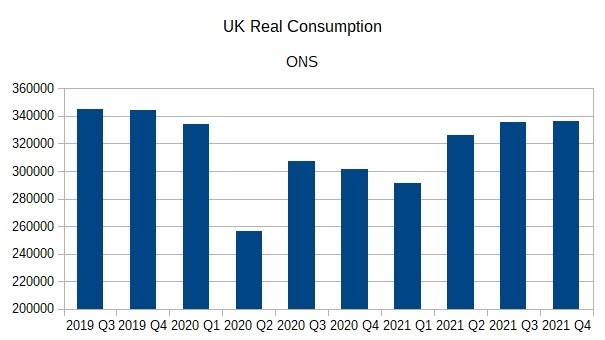

This is exactly what we saw in the

Autumn of 2020. Thanks in part to pressure from Sunak, the government

rejected advice from the experts to impose a full lockdown, and so

infection numbers grew and consumption remained over 10% below its

end-2019 level. When a sustained lockdown came in 2021Q1 consumption

was only a few percentage points lower than 2020Q3 (GDP was actually

higher), but that lockdown brought cases right down, and vaccines

then removed the need for further lockdowns.

It is really difficult to rationalise

what Sunak did during the summer and autumn of 2020. By deliberately

not asking SAGE about the impact of EOTHO, he must have known this

would increase infection rates. Did he really think the economy would

be largely unaffected by a second wave? Unlikely, as in enacting

EOTHO he was aware of people reducing social consumption because of

the pandemic! Perhaps his actions were guided by perceived political

advantage rather than economic or health impacts.

Gross incompetence is a strong term,

but I fear it clearly applies to Sunak in these two cases. His

thinking appears not to have got beyond the level of a right wing

newspaper column, despite having the resources of the Treasury at his

disposal. [3] His actions not only led to many people dying, but his

actions also damaged the economy when he was the minister in charge

of protecting it.

[1] This response modelled in our paper

involves individuals trying to avoid catching the virus. It was not

coordinated by governments in any way. In the paper we didn’t look

at government imposed lockdowns beyond school closures.

[2] Obviously this judgement is country

dependent. In countries where people and employers are better

informed and more socially minded, unofficial lockdowns may come

closer to replicating official lockdowns. This is why comparisons

between countries that did lockdown and Sweden are potentially

misleading, and why comparisons between Sweden and other Scandinavian

countries are much more informative.

[3] Reporting on the Covid inquiry has

naturally focused on political culpability rather than the advice

politicians were being given. In this particular case it is

inconceivable that the Treasury was unaware of the analysis I outline

here. What happened to that analysis, and how far up the civil

service hierarchy it got, are interesting questions we do not know

the answer to. Until we know, we can only wonder whether senior Treasury officials’ concern about higher government borrowing in lockdowns mattered more than the health of the economy.