Europe will have to rely on US fossil fuels for decades to come as it races to diversify from Russian natural gas and scale up its renewables sector to boost energy security, the EU’s top energy official has said.

Ditte Juul Jørgensen told the Financial Times that the EU had “the instruments that we need” to endure another winter energy crisis in the aftermath of the Russia-Ukraine war. These included conservation and more renewable energy.

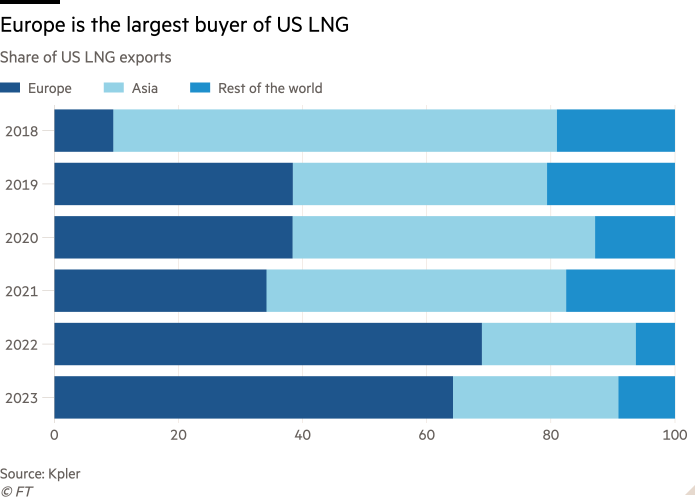

But she said the bloc’s reliance on exports of US liquefied natural gas would persist.

“We will need some fossil molecules in the system over the coming couple of decades. And in that context, there will be a need for American energy,” said Jørgensen, director-general for energy in the European Commission, in an interview in New York.

The statement is one of the strongest signals from Brussels that EU states will consume US LNG well past the end of the decade in spite of concerns expressed by some politicians and environmental campaigners that it could dent the bloc’s ambitious climate goals.

Brussels is walking a tightrope between its need to boost energy security by weaning itself off Russian gas and reaching goals of net zero carbon emissions by 2050 and cutting emissions by more than half by 2030 compared with 1990 levels.

After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year, the EU struck a groundbreaking pact with the Biden administration to work towards securing an additional 50mn cubic metres a year of US LNG until at least 2030. The agreement was made on the basis that it was consistent with EU and US climate goals and both parties would work towards reducing gas demand.

Analysts say that Jørgensen’s statements will help “clear the path forward” for European buyers who have been hesitant to sign deals with US suppliers past the 2030 timeframe.

“For US developers trying to line up deals, it’s a really positive signal for them,” said Fauzeya Rahman, an LNG analyst at consultancy ICIS.

US exports of LNG to the EU more than doubled last year, rising to 56 bcm in 2022, from 22 bcm a year earlier. At the end of 2022, Russian gas accounted for 16 per cent of the EU’s gas imports, down from 37 per cent in March 2022.

While Russian pipeline flows have tailed off, LNG shipments from Russia to Europe have been at record highs.

Earlier this month, Belgium’s energy minister Tinne Van der Straeten urged the bloc to cut off imports of Russian gas.

US LNG companies, which condense gas for loading on to ocean tankers, have continued to sign new long-term supply deals with Europe.

Cheniere Energy, the largest US LNG exporter, has agreed two contracts with Europe-based Equinor and BASF this year, promising to deliver 2.55mn tonnes a year across the Atlantic into the 2040s.

“We continue to see significant need for natural gas in Europe for decades, especially for end users who value long-term partnership and security of supply,” said Anatol Feygin, Cheniere’s chief commercial officer.

Venture Global LNG, another US exporter, signed a 20-year contract to deliver 2.25mn tonnes a year of the fuel to German state-owned company SEFE, or Securing Energy For Europe, in June. Together with its 20-year contract with EnBW signed in October, Venture Global is expected to be Germany’s largest LNG supplier.

But there is growing concern among some European politicians and campaigners that building gas import terminals and entering into long- term contracts with US suppliers will put the EU’s climate goals at risk.

“Increased fossil fuel infrastructure runs counter to this goal,” said Ciaran Cuffe, an Irish Green MEP.

“It’s short-sighted to increase our dependence on LNG and fracked gas, full stop. Ultimately, our focus has to be on reducing our reliance on fossil fuels. Boosting the take-up of renewables is a priority, and it is already exceeding expectations,” he said.

The Irish planning board last week refused to approve the construction of a floating LNG import terminal by US-based New Fortress Energy, saying that it would be “inappropriate” ahead of a review of the country’s energy supply.

Eamon Ryan, Ireland’s minister for environment, who is a member of the Green Party, said the future is not with fossil fuels. “At a time when the world is burning, we cannot expand our use of gas.”