France has

12 high speed train lines, and is planning to build 4

more. Spain has even more. Yet the only high speed line the UK

currently has leads out of the country. Our Prime Minister, without

apparently consulting anyone, has cancelled the more useful part of

our second high speed line to Manchester. As Tom

McTague writes: “The man from Goldman Sachs looked

at the books and made a decision — and we are all supposed to

accept that this is how we are governed.”

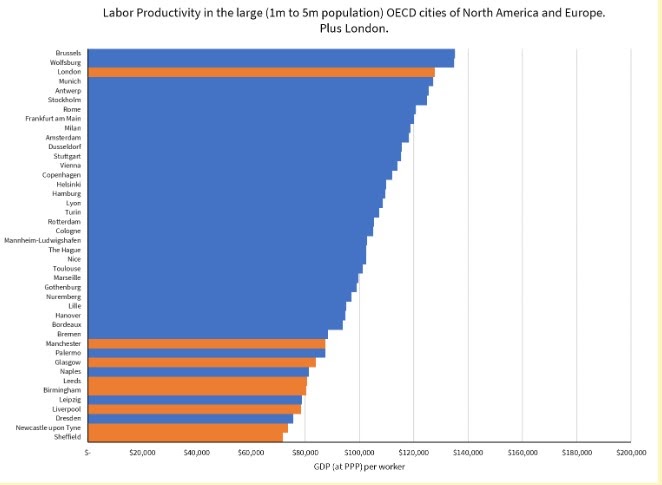

In economic terms

the UK is essentially a country of two halves: the South East with

London at its centre, and the rest. Below is a crucial chart taken

from this

post by Tom Forth, showing productivity levels in

Europe’s major cities.

Near the top is

London with other capitals as you might expect, but in the middle we

have the other major cities of France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands

and Belgium. At the bottom are the UK’s major cities. As Forth

shows in his blog, this regional divergence in the UK has steadily

increased over the last two decades, but as some other European

countries show this is far from inevitable.

If you want to know

why the performance of the UK as a whole has declined over the last

decade and a half compared to most other major economies, here is a

place to start. It is a mistake to see ‘levelling-up’ as just a

distributional issue. When most of the country isn’t working very

well, it is not surprising that the country as a whole performs

badly.

A big reason for

this poor performance is poor connectivity. Not just connections to

London, but also connections between cities and between the cities

and surrounding areas. The point of HS2 was not to get from London to

Manchester faster (a very London-centric point of view), but to

create greater capacity for more local passenger trains and freight

on the existing lines. The most useful part of the HS2 project was

not London to Birmingham, but the additional legs from Birmingham,

which are the lines that have been cut.

The excuse Sunak

used for cancelling the Manchester leg of HS2 was that since the

pandemic people were using trains less. Demand had shifted down he

argues, perhaps because more people were working from home or using

zoom for meetings. Yet what evidence is this based on? Here is the

latest quarterly

data for the total number of rail journeys in Great

Britain.

It is true that in

the first quarter of this year total journeys were still less than

pre-pandemic, but the numbers have been steadily rising over the last

few quarters. It is way too soon to declare that there has been a

fundamental shift in rail usage. [1] The suspicion

has to be that the real reason for taking that

decision now is to ‘make room’ for tax cuts before the next

election, where the space they are making room in is a stupid

fiscal rule on

top of unrealistic forecasts.

Evidence that this

was a hasty short term decision to save money rather than any long

term strategic plan comes from the raft of measures assembled to

suggest that ‘every penny of the money saved’ will be spent on

other transport projects for the north. The most embarrassing is that

it included a commitment to establish

a rail link that already exists, but there are plenty

of other contenders for that top spot. That suspicion

also comes from the spin: if No.10 says they are focused on the long

term that means they are doing the opposite and are hoping the spin

will cover that up. Put this together with his various measures to

make it even more difficult for the UK to hit its net zero targets,

and we have a Prime Minister personally taking decisions for the

benefit of his own short term future and to the detriment of the UK

in the longer term.

Cancelling HS2, and

rolling back on net zero, are two vivid examples of a long term UK

problem that has become acute since 2010. The government does not

invest enough, and partly as a result the private sector does not

invest enough. As this

excellent report from the Resolution Foundation’s

Felicia Odamtten & James Smith shows, public and private sector

investment are complements; the former encourages the latter. This

chart from the report shows that UK public investment is consistently

below the international average, and that average includes many

countries that have underinvested over the last two decades like

Germany and the US.

Before the financial

crisis the impact of this lack of public investment on UK economic

growth was masked by other positive factors (e.g. EU membership and

the single market). Pretty much everything the government has done

since 2010 has made this situation worse. Under the Labour government

net public investment (the chart plots gross not net) increased from

0.5% of GDP to 3.0% of GDP, but 2010 austerity involved a sharp cut

back in public investment to 1.5% of GDP. It briefly returned to 3%

of GDP in 2020, but is now declining and is expected to decline

further.

You can see that

lack of public investment pretty well everywhere you look. The impact of this on the economy is

not just about infrastructure like roads and rail. We have an acute

shortage of hospital beds, way below most other OECD countries in per

capita terms, and less equipment like MRI machines than most other

OECD countries. That leads to a less healthy population and therefore

to a reduced and less productive workforce.

But as the

Resolution report also points out, stability in decisions is also

important. Building new infrastructure will encourage private

investment once it’s built, but you would hope (given how long

these things take to do) that the announcement of infrastructure

plans would also encourage private investment (which also can take

some time to create). If you keep changing plans, or overturn the

expectations business has of what governments will do, you increase

doubt and uncertainty which in turn discourages research and

investment. Here lies one of this government’s biggest failures,

and it began in 2010.

Recessions happen,

but the UK experience of the postwar period is that governments would

do what they could to generate strong recoveries from recessions as

quickly as possible. In the UK in particular, it is remarkable how

quickly growth returned to its long term trend after each economic

downturn, and a major reason for that was Keynesian countercyclical

policy (monetary or fiscal). That gave business the confidence to

plan ahead and invest.

Cameron/Osborne

changed all that. With austerity they did the opposite (with monetary

policy largely out of action), and so the recession led to a shift

downward in GDP. There was no recovery for three years, and it was

tepid when it came. From that point on every business knew that their

plans had to allow for future recessions which might also lead to

permanent shifts down in UK output.

The next rug to be

pulled out from the legs of businesses operating in the UK was of

course Brexit. Not only was any business importing or exporting from

or to the EU hit by making it more difficult to trade, but the UK

also lost its attractiveness for any potential foreign direct

investment looking to access the Single Market. Ending free movement

meant that inflation in the UK following the pandemic was worse than

elsewhere, requiring tougher measures from the Bank Of England.

But through all

this, the government kept its commitment to net zero, and to HS2.

Businesses producing greener products (from energy to cars) knew that

there would be an expanding market coming soon for their products.

They could base their business beyond the South East of England,

knowing better communications were on their way. Now, with a stroke

of Spreadsheet Sunak’s pen, this rug has been pulled away too.

Measuring the impact

of policy uncertainty on UK investment and R&D is not easy, but

recently some studies have attempted to do that. [2] They confirm

that greater policy uncertainty reduces both innovation and

investment, and that policy uncertainty has on average been

significantly higher over the last decade and a half than during the

previous decade. Sunak’s decision to end the commitments to HS2 and

net zero in an effort to obtain some political gain just continues a

pattern we have seen since the Conservatives took charge of economic

policy thirteen years ago. Uncertainty generated by this government’s

economic policy changes are an important factor behind the UK’s

relative economic decline over the last fifteen years, and Rishi

Sunak’s administration has turned out to be as bad as his predecessors in this

respect.

[1] The number of

passenger miles travelled has been flat over the last four quarters,

but that is still far too flimsy a foundation for such a major

decision.

[2] The seminal

study is Baker, Bloom and Davis (2016), QJE 2016. Their Economic

Policy Uncertainty index (a more recent version is here)

shows uncertainty stepping up around the Global Financial Crisis

period, and staying higher subsequently.