Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

The top half of the highest-earning US households have increased their ownership in financial assets to near all-time highs, leaving them ever more exposed to rising inflation. Bonds and especially stocks are thus acutely vulnerable to a re-acceleration in price growth.

Ronald Reagan called inflation as violent as a mugger, as frightening as an armed robber and as deadly as a hitman.

If that’s so, then it seems the biggest-income households in the US are the most fearless – or the most foolhardy.

Financial assets, principally stocks and bonds, are not where you put your savings if you think inflation’s going to be a problem. And yet the best-off households have been increasing their financial-asset exposure, with the wealthiest increasing their allocations by the most (in the period from last summer when the Federal Reserve started raising rates to March this year, the latest data point in the Fed’s data).

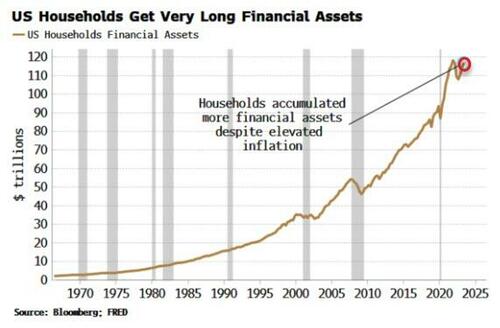

In numbers terms, the 90th to 99th-percentile top households by income (those earning ~$210k-$570k per year) increased their holdings of financial assets the most, by over $1.5 trillion to $43 trillion between 2Q22 and 1Q23. The least well-off households (those in the bottom half, earning under $70k a year) saw the smallest increase, only $36 billion, taking their total to $2.5 trillion.

The wealthy’s insouciance to inflation has led to the household sector’s exposure to financial assets rising to a near record, almost $117 trillion. This fell briefly when US inflation was rising, but began climbing again when inflation started falling from its peak. Households clearly took Fed Chair Jay Powell at his word that he’s a Paul Volcker, not an Arthur Burns.

Financial assets consist of bonds, bank deposits, money market funds (MMFs) and corporate and non-corporate (i.e. unlisted) equity. Its rise has been driven by listed stocks and bonds, again with the wealthiest households accumulating the most.

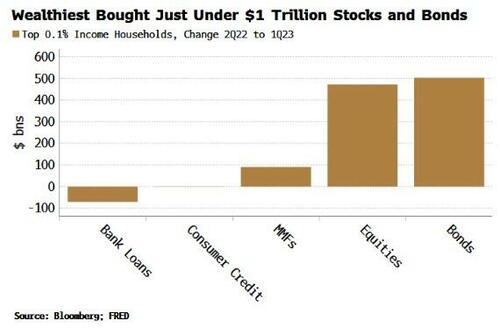

The top 0.1% of households, who have at least $38 million of annual income, added over $1 trillion in stocks and bonds between 2Q22 and 1Q23. They also added some exposure to MMFs, while they reduced their bank-loan exposure on a net basis. Better a receiver than a payer when rates are higher, if you have the means to make it so.

The next wealthiest households similarly added stocks, bonds and MMFs to the tune of around $1.6 trillion, while also increasing their consumer credit a smidge.

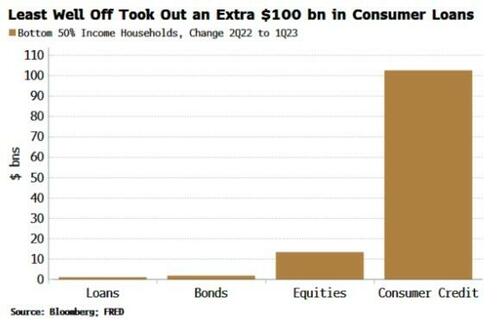

It’s a very different story for the least well-off. The bottom half of households own the smallest amount of financial assets, so it’s not surprising their increase in stocks and bonds has been minimal. However, the $100 billion rise in consumer credit, taking the total to $2.7 trillion, is quite startling.

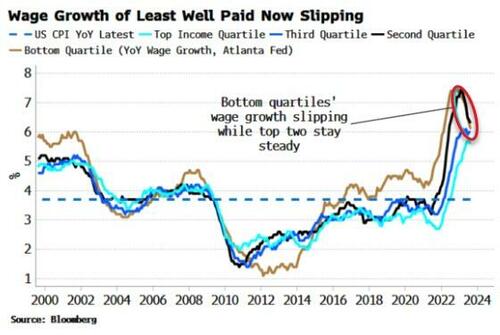

This jump is especially noteworthy when you factor in that it was the lowest paid who were (for a change) seeing the fastest wage rises. Now though, the wage growth of those in the bottom quartiles is falling the most, meaning that their reliance on credit will rise – just as borrowers are facing more difficulty from banks tightening lending standards.

So while the wealthiest have been adding to duration through stocks and bonds, the least well-off have been increasing their net borrowing – i.e. in effect getting longer inflation while the richest have been getting shorter.

(This is from an asset and liability point of view rather than an income and spending one, where the least well-off remain most exposed to price rises).

More financially-pinched households, especially when we are in the world of the Treasury put, are likely to put further pressure on the already-swollen fiscal deficit, which would fan the inflation flames yet more. And that’s before we’ve had serious job losses and a recession.

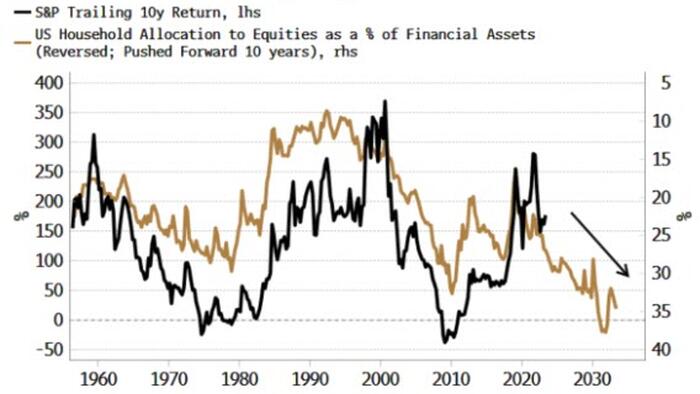

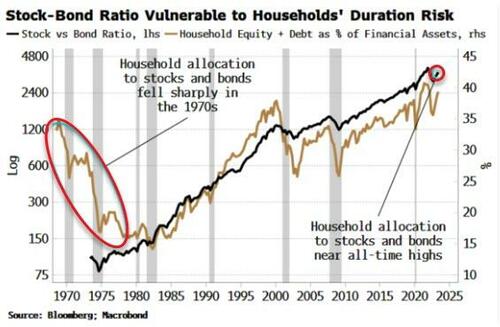

Either way, asset markets are very exposed to a re-acceleration in inflation, something I think is more likely than not. Households’ allocation to stocks and bonds fell precipitously in the inflation-ridden 1970s, while today it remains near highs.

Households’ bond allocation fell in that decade, but it was the decline in the allocation to stocks that was the most dramatic.

It fell from 27% of financial assets in the late 1960s to only 8% in the early 1980s as high inflation swindled equity investors.

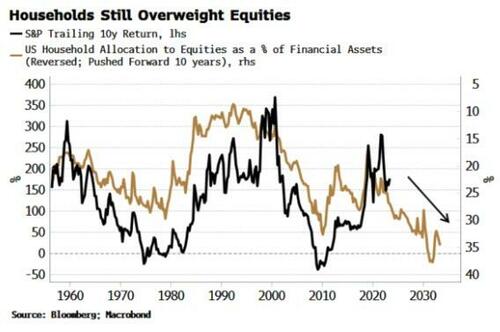

Typically, high allocations to equities are followed by sub-par returns over the long term. We saw this through the 70s, and we are likely to see it again in the coming years as currently elevated equity allocations fall as the wealthiest households take fright at inflation’s return, and reduce their exposure to stocks.

Warren Buffett said that inflation has a fantastic ability to simply consume capital. The wealthy are taking a huge wager their capital will not face that ignominious fate.

Loading…