Kids not being able

to go to their normal school because those schools are crumbling away

is as good an example as any of the impact of 13 years of austerity

government. It began with Gove scrapping Labour’s Building Schools

for the Future programme (a decision he subsequently

said was one of the worst he made) when the

Conservatives came to power in 2010, and it may well end with

thousands of children being forced to relocate to temporary

accommodation because Sunak when Chancellor failed to respond to

warnings from his own Education department.

It is also an

example of the impact bad fiscal rules can have. As I have argued

many times, whether to undertake public investment (which can vary

from large infrastructure projects to replacing crumbling concrete)

should depend on the merits of the investment, and not on some

arbitrary aggregate limits. Yet governments have at various times

imposed fiscal rules that either included public investment (a target

for the total deficit, or a falling debt to GDP target) or in some

cases imposed a limit on total public investment itself. [1]

The case of

crumbling schools caused by RAAC concrete also clearly shows why

arbitrary aggregate limits on public investment make no sense. When

the

roof of a primary school in Kent collapsed in 2018, ignoring the

problem became, in

the words of the National Audit Office, a “critical

risk to life”, which meant many schools with Raac concrete in them

needed replacing fast. That means spending a lot of money quickly. As

we now know, and as the Treasury were told, not doing so would mean

some school buildings would become unsafe to use. Unlike current

spending on day to day services, the need for public investment can

vary substantially over time, and sometimes that investment just has to take place.

What did Sunak, or

the Treasury, expect to happen when they revised down a RAAC based

bid from their education department by a factor of 4? Were they

crossing their fingers and hoping that the engineers were being over

cautious, and that no more buildings would collapse? Or did they not

even get as far as reading what the department had written, and

instead just looked at numbers on a spreadsheet? Did no Treasury

official raise their hand and say ‘but minister, what will happen

when they start closing schools because they are unsafe’?

The term ‘Treasury

brain’ is fashionable, but if the politicians in charge are

determined to spend less public money then the Treasury can do little

to stop them. Furthermore, these politicians are invariably short

term in their political outlook, so they will always be tempted to

cut investment rather than current spending. Investment by its nature

has its benefits in the future, while current spending cuts will be

noticed today. This is why it’s important to design fiscal rules

that stop politicians doing this. If the Treasury can tell a minister

that cuts to public investment will not do anything to help that

minister meet their fiscal rules, they are less likely to make those

cuts. [2]

The same is true for

short term cuts that end up costing more in the longer term. Treasury

brains are more than capable of seeing the foolishness of doing this,

but if the remit from politicians is to get down borrowing over the

next few years by whatever means possible, Treasury civil servants

cannot keep options from politicians. Again fiscal rules need to be

medium to long term, to avoid this kind of foolishness.

The whole current

system, where dangerously crumbling concrete is kept in place because fixing it

would require some borrowing, is predicated on a kind of deficit

fetishism that treats reducing government borrowing as more important

than almost anything else, including teaching children. Politicians

are putting reduced borrowing ahead of essential investment. Asked

why, they will mutter phrases like ‘fiscal responsibility’, and

the media will find a City economist to talk about ‘bond market

jitters’. Someone will mention the Truss fiscal event, as if

borrowing to stop schools collapsing on children can be equated to

cutting the top tax rate. (In reality the reaction to the fiscal

event was

all about interest rate uncertainty and pension funds

taking risks rather than excessive government borrowing.)

Fiscal

responsibility does have a real meaning. It makes sense to ensure

taxation matches current spending in the long run so debt to GDP

levels are sustainable. Fiscal rules are useful to prevent

politicians cutting taxes or spending more to win elections and

funding these giveaways by borrowing. But refusing to borrow to

enable schools to remain open and safe is clearly not in any sense

fiscal responsibility. For once household and firm analogies are

appropriate. People borrow if necessary to fix serious problems with

their homes, and firms would of course borrow to prevent their

factories falling apart, so why not the government when it can borrow

more easily and more cheaply than any household or firm?

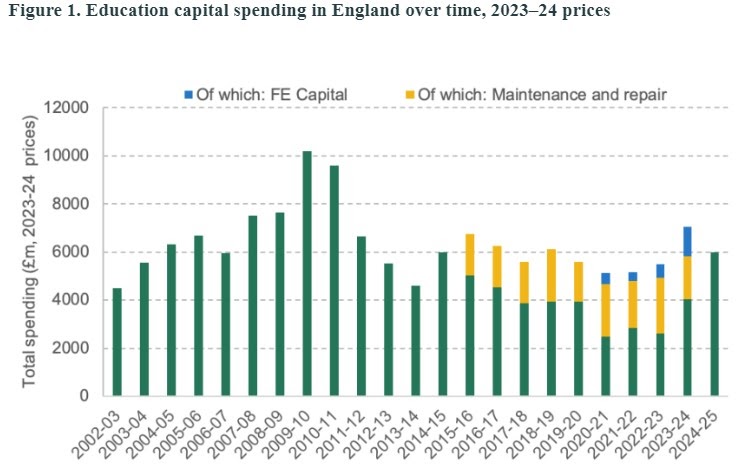

However there is one

area where aggregate conditions, rather than the individual merits of

any investment, does matter. This is borrowing costs, which should

influence when (not if) investment is done. The

ideal time to start replacing RAAC concrete was when borrowing costs

were almost zero, because short term interest rates were at their

lower bound. Yet, as this graph from the IFS shows, this government

cut capital spending on education compared to levels under Labour,

just at the point when borrowing costs were at their lowest. Cutting

investment when borrowing is cheap, and being forced to do the

investment when borrowing costs are much higher, is a good example of

this government’s economic incompetence.

This is one area

where the way the Treasury does things may be lacking. Whether a

project is worth doing is typically assessed using a constant 3.5%

real discount rate, with some exceptions. There are good arguments

for using a discount rate independent of market rates, although

whether the rate should be as high as 3.5% is another matter. But

deciding that public investment projects are worthwhile to do, and

deciding when to do them, are two different choices. The latter will

depend on many things, including the state of the economy and the

cost of borrowing.

It is obviously

cheaper for the government to undertake a worthwhile investment when

the cost of borrowing is very low. Yet it is unclear how that basic

point influences government spending decisions. Needless to say, a

focus on reducing borrowing when the economy is depressed, and

interest rates and borrowing costs are likely to be low, is

completely the wrong thing to do. But even if that was not the case,

it is not clear that Treasury practice encourages investing when it

is cheap to borrow.

Closing schools

because the government refused to replace crumbling concrete is also

a perfect example of what this government has become in another

sense. Before the 2020 spending review, Sunak as Chancellor was told

by the education department that at least 300 schools needed

replacing a year because of crumbling concrete, and they asked for

funding to replace 200 a year in the first instance. Instead Sunk

decided to halve the school rebuilding programme target from 100 to

50 schools per year. But when presenting the results of this spending

review, he

described it as producing a “once in a generation

investment in infrastructure”. It’s not just that they lie all

the time, but when Sunak like Johnson makes grandiose claims it is

generally to disguise monumental failure.

Unless something

unforeseen happens, we are destined for a year when all we can do is

look forward to a change in government. An incoming Labour government

may not have the same aversion to the public sector as this current

lot, but they will still have fiscal rules. The government will still

be working in a media environment where government borrowing is

viewed with suspicion, and the distinction between how day to day

spending and investment is funded is rarely made. Labour are

committed to borrow to invest, but are saddled with Conservative fiscal plans that

are unworkable and a falling debt to GDP rule that discourages

investment. Rachel Reeves’ priority in government should

be to raise taxes to match increases in day to day

spending, and to scrap

the falling debt to GDP rule so that we can start

investing in the public sector after a decade and a half of complete

neglect.

[1] That limit, of

3% of GDP, has now become redundant as the share of public investment

is planned to fall to almost 2% in five years’ time. (Public

investment reached 3% of GDP three times in recent financial years:

2008/9,2009/10 and 2020/21.

[2] It would be nice

to say that good fiscal rules that excluded public investment would

completely avoid austerity driven cuts to that investment, but

unfortunately the experience of the Coalition government suggests

that is not true. As I noted many times, the structure of the primary

fiscal rule first introduced by George Osborne did exclude public

investment, because it had a target for the current balance (the

total deficit minus net investment). As a result, there was no need

for the Coalition government to cut public investment, yet that is

exactly what they did, particularly in 2011 and 2012. That decision

alone cost the average household thousands of pounds in lost

resources.

It was this cut in

public investment that really hit the UK recovery from the Global

Financial Crisis recession. Quite why the Coalition government

decided to cut public investment so drastically when it did nothing

to meet their fiscal objectives is unclear. Did the Treasury just ask

departments to cut all spending, and naturally (see above) these

departments initially chose investment over current spending? Or did

the Chancellor not understand his own fiscal rule?

This is why I

hesitate to claim better fiscal rules might have prevented this

government cutting back on public investment. When politicians have

an ideological belief that everything in the public sector is

inefficient and wasteful, they may ignore even the most enlightened

fiscal rule.

Equally when fiscal rules become things that are changed every couple of years, as they have been since 2015, then unfortunately it also tempting for politicians that know they are nearing fiscal limits to include public investment in any target, because it is easy to cut.