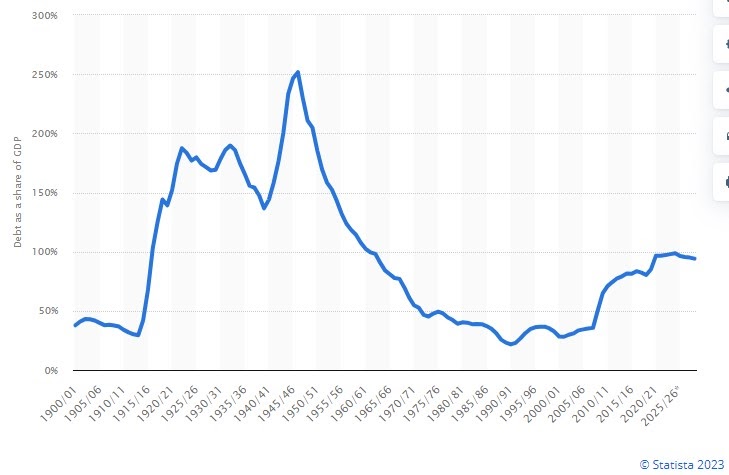

As the chart below

shows, the story of UK government debt since 1900 (as a share of GDP)

is a story of crises (source).

The ratio of debt to

GDP rose rapidly during WWI, stabilised thereafter and then started

to fall in the second half of the 1930s, only to rise again during

WWII. After WWII it fell slowly but steadily, returning to pre-WWI

levels by the end of the century. It rose again during and after the

Global Financial Crisis, finally rising a bit more during the

pandemic.

As I

explained here recently, government debt is a device

that avoids sharp changes in taxes or government spending during bad

times. It is therefore entirely right that during a crisis, like a

world war or a financial crisis, government debt should increase

substantially. To put it simply, the alternative of raising

everyone’s taxes sharply would only compound the negative impact of

the crisis.

For example if

governments had raised taxes during the 2009 recession then the

recession would have been even worse than it was. Consumers would

still have increased savings and reduced borrowing during the crisis,

so consumption would have fallen further than it did because taxes

were higher. When governments did try to reduce their own spending

and raise taxes after 2010, it caused considerable damage.

It was therefore

natural for governments around the world to treat the Covid pandemic

as just the kind of crisis where government debt needs to rise, to

help pay for additional government spending during the pandemic. In

Europe that additional spending was mainly paying large sections of

the workforce to stay at home (furlough), while in the US it involved

much higher unemployment benefits and other payments.

I will take the case

for additional government spending during the pandemic as given. This

is not yet another post from me about the wisdom of early but

comprehensive lockdowns before vaccines became available. What I want

to ask here is whether the reaction of most governments to keep taxes

unchanged was correct? The reason that question should be asked is

what happened to household savings during the pandemic. Here is the

UK, and you will see a similar pattern in other countries.

In financial terms,

the pandemic was not hard for most (not all) households. Instead most

ended up saving much more than normal. The reason is straightforward,

and goes back to something I have written

a great deal about: social consumption. Most people

substantially reduced their spending on activities like going out to

the pub, restaurants, entertainment and travel. Sometimes this is

because they were told to do so, but there are good reasons to

believe this would have happened to a considerable extent anyway as

people tried to avoid getting the virus from others. Social

consumption amounts to about a third of total consumption, so it was

inevitable that most households ended up saving a great deal during

the pandemic.

There was therefore

substantial scope on average for governments to pay for their

additional spending during 2020 by temporarily raising taxes rather

than increasing government debt. Most consumers would not have had to

reduce their consumption further because they were paying higher

taxes. Instead these taxes would have simply taken the place of large

increases in personal savings during the pandemic.

If the pandemic was

not like previous crises in that there was scope for the government

to raise taxes temporarily in 2020, that does not necessarily imply

that is what they should have done. For example higher taxes of

whatever type will not perfectly match to reductions in social

consumption, so there might be important distributional problems in

raising taxes. Higher taxes might have discouraged some from working

whose work was vital to keep the country going. Perhaps higher taxes

would have reduced social solidarity at a time when it was most

needed.

Whatever your view

on this, I hope it suggests that higher government debt during a

crisis is something that needs justification rather than something

that should happen automatically. But strangely we do not seem to be

having this conversation about the biggest global crisis facing the

world today, which is climate change. So far at least the need to

green the economy has not led governments to pay for that spending

using deficit funding. I

have talked on previous occasions about why climate

change, and the need to green the economy to reduce carbon emissions,

should be considered as a crisis which requires increases in

government debt. Yet very recently we have seen the German

courts prevent their government from increasing debt

to pay for financing climate change expenditure.

The case for using

deficit finance to pay for greening the economy is far stronger than

paying for furlough during the pandemic. Although in theory carbon

taxes fit the polluter pays model, the reality is that government

spending and financial incentives have

been much more effective at encouraging green energy

production. As with most government investment, it is not clear why

the current generation should pay for something that will mainly

benefit future generations.

Why do some

within Labour worry about the Conservatives

weaponising their £28 billion a year pledge on green investment, and

propose cutting back on those plans? Perhaps its because throughout

most of the media, reducing government debt is either considered more

important than preventing climate change, or the two are not

connected in people’s minds. I want to propose a collective New

Year resolution. If anyone claims that it is important for this or

the next government to reduce their debt to GDP ratio, please someone

ask why climate change isn’t the kind of crisis that should see

government debt rise?