Equity investors are always looking for signs of the next recession. Recessions mean higher unemployment, lower spending, lower earnings and ultimately more defaults, all of which are bad news for stock prices. Hence, investors continuously scrutinize macroeconomic data, earnings numbers, valuations and sentiment levels, among other indicators, to assess whether another downturn is coming. Unfortunately, the relationship between these indicators, recessions and stock market prices is far from straightforward. As it turns out, equity markets are far less forward-looking than one might expect.

The yield curve, the ultimate recession indicator

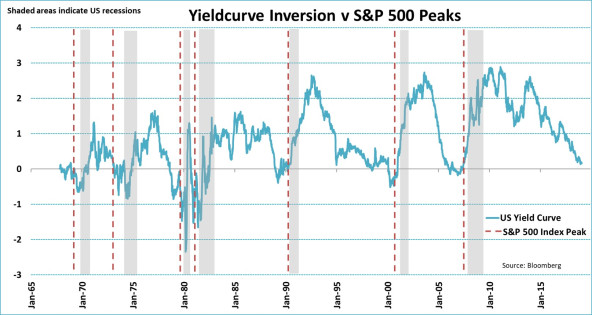

The US yield curve showing the difference between long-term and short-term bond yields is one of the best – if not the best – recession indicators out there. The yield curve correctly predicted all the last seven US recessions since December 1969. As a rule of thumb: whenever the yield curve inverses, meaning when short-term rates move above long-term rates, a recession will occur somewhere within the next year or two.

However, an inverted yield curve has not stopped the S&P 500 Index from rising, as shown in the chart above. The blue line reflects the shape of the yield curve, while the red, dotted lines reflect the S&P 500 Index peaks before the next recession. If we take a closer look, the chart reveals that stock prices kept rising after each time the yield curve inverted, except for in 1973. In fact, the S&P 500 Index continued to grind higher for another 11 months, or almost a year, on average, before it reached its peak. The S&P 500 Index climbed by roughly 8{01de1f41f0433b1b992b12aafb3b1fe281a5c9ee7cd5232385403e933e277ce6}, again on average, during that time. So, while the yield curve is perhaps the ultimate the recession indicator, it does a poor job in predicting stock market peaks. You would have missed a significant amount of return if you had based your investment strategy on the yield curve.

Other forward-looking indicators, like for example, the ISM Manufacturing Index, which has a solid track record in forecasting future GDP growth, also lack forecasting power related to stock market performance surrounding recessions. Whenever the ISM index falls significantly below 50, traditionally seen as the dividing line between positive and negative future economic growth, it reliably signals a recession. But for stock market returns the results are mixed. On average, calendar months with the lowest readings of the ISM Manufacturing Index are followed by the highest 12-month forward return. But the results vary quite a lot with the direction of the ISM Index and the duration of the upcoming recession.

Valuation as an indicator

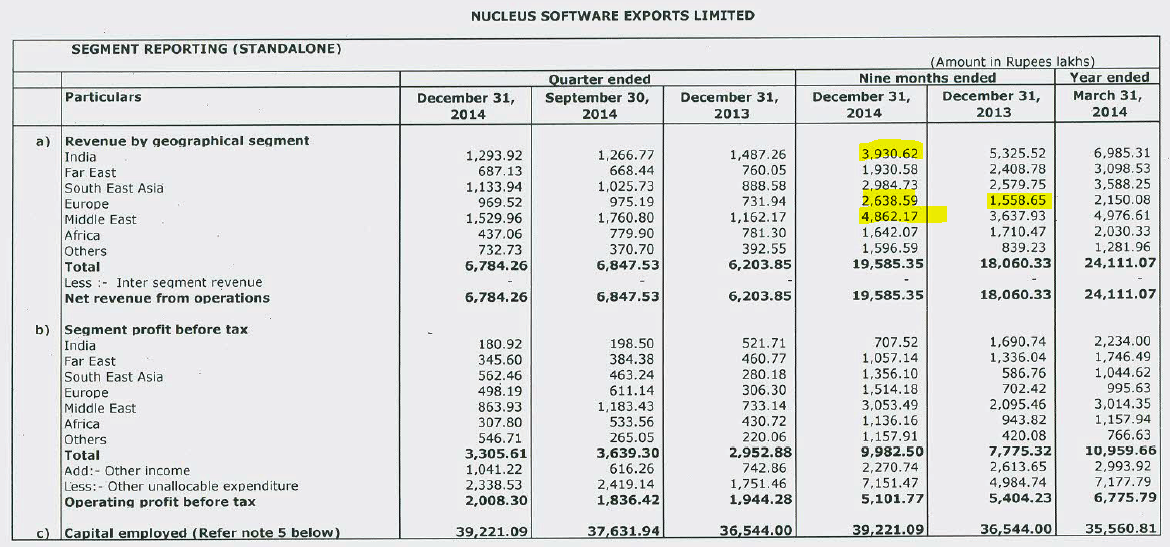

So, what about valuation? Some investors believe that high valuations precede recessions, and that stocks fall during them as normal valuation levels are restored. The rationale behind this is that most economic cycles end in bubbles. For example, if monetary policy is too loose for too long, companies over-invest, driven by the prospect of ‘never-ending’ growth, or because growth is financed to an increasing extent by debt. All of these scenarios result in a stellar rise in stock market valuations, which at some point must be corrected.

While it is true that numerous recessions are the result of the bursting of a bubble, this does not automatically involve high stock market valuations. In fact, recessions happen at any level of valuation. As the chart above shows, price/earnings (P/E) ratios of the S&P 500 Index have varied greatly just before the start of past recessions. If anything, P/E ratios were somewhat below the long-term average ahead of a recession. Perhaps it is the vivid memory of the bursting of the Internet bubble, and the economic downturn that followed it, that gives investors the idea that high equity valuations are a characteristic of future recessions. But while that valuation-induced downturn was certainly remarkable, and is still referred to on regular basis, it was also rare. This does not imply that valuations are irrelevant for future returns. When valuations are high, risk premiums are low, which leads to lower returns on a longer-term horizon. This is one reason for why we believe that shifting some equity exposure out of the relatively expensive US in the coming year(s) makes sense.

Imminent

As you may have already deduced from the first chart, equity markets tend to peak not that long before recessions. If we look at last seven US recessions again, the S&P 500 Index recorded a peak just six months before the official start of the recession, on average. This is shown in the chart below. On two occasions, in 1980 and 1990, the peak in the equity market actually coincided with the start of the recession. In general, equity markets tend to perform solidly up to 12 months before a recession, then show a mixed but positive picture 12 to 6 months before a recession, and then tend to turn south within six months of the next recession.

A couple of things should to be considered, however. First, the number of recessions, fortunately, is limited. But this also decreases the significance of past-return data. In addition, recessions are often defined months or sometimes even years after they occur. At the time of a market peak, investors did not know yet when the recession would officially start. Yet, this does not take away from the fact that equity markets tend to peak long after renowned recession indicators signal one. This in turn explains why these indicators have little forecasting power when it comes to stock market prices.

So, when is the next recession?

Unfortunately, it’s pretty difficult to pinpoint exactly when the next US recession will hit. This is neatly demonstrated by the poor predictive track record of institutions like the IMF, the World Bank and even the Federal Reserve. Having said that, based on the latest macroeconomic data it could take a while before a new recession occurs. The US labor market remains extremely strong, creating a significant number of new jobs each month. At the same time, people are re-entering the labor market, reducing inflation risks. Wages are rising faster than inflation, which increases the purchasing power of US consumers.

In addition, the ISM Manufacturing Index unexpectedly rose to a healthy 56.6 in January, suggesting above-average GDP growth going forward. All of this is happening with the Federal Reserve on a clear hold for its tightening cycle, limiting the drag on the economy and supporting financial conditions. China remains the most important external factor for the US economy, especially since the trade dispute between the two countries remains unresolved. China too, however, feels the negative impact of slower trade, and is stimulating its economy. Together, these developments reduce the probability of a US recession this year. Therefore, given the limited forward-looking ability of equity markets when it comes to recessions, the odds favor higher stock market prices over lower stock market prices for now.

This blog was derived from the Theme of the Month in the Robeco Monthly Outlook for February (click here to go to the Outlook).

If you wish to receive these blogs and my Daily Sketch by mail, please subscribe here https://eepurl.com/gaJBqn

SOURCE: Jeroen Blokland Financial Markets Blog – Read entire story here.