My discussion

about current inflation two weeks ago focused on the UK. Over a year

ago I wrote

a post called “Inflation and a potential recession

in 4 major economies”, looking at the US, UK, France and Germany. I

thought it was time to update that post for countries other than the

UK, with the UK included for comparison and with Italy added for

reasons that will become clear. I also want to discuss in general

terms how central banks should deal with the problem of knowing when

to stop raising interest rates, now that the Fed has paused its

increases, at least for now.

How to set

interest rates to control inflation

This section will be

familiar to many and can be skipped.

If there were no

lags between raising interest rates and their impact on inflation

then inflation control would be just like driving a car, with two

important exceptions. Changing interest rates is like changing the

position of your foot on the accelerator (gas pedal), except that if

the car’s speed is inflation then easing your foot off the pedal is

like raising rates. So far so easy.

Exception number one

is that, unlike nearly all drivers who have plenty of experience

driving their car, the central banker is more like a novice who has

only driven a car once or twice before. With inflation control, the

lessons from the past are few and far between and are always

approximate, and you cannot be sure the present is the same as the

past. Exception number two is that the speedometer is faulty, and

erratically wobbles around the correct speed. Inflation is always

being hit by temporary factors, so it’s very difficult to know what

the underlying trend is.

If driving was like

this, the novice driver with a dodgy speedometer should drive very

cautiously, and that is what central bankers do. Rapid and large

increases in interest rates in response to increases in inflation

might slow the economy uncomfortably quickly, and may turn out to be

an inappropriate reaction to an erratic blip in inflation. So

interest rate setters prefer to take things slowly by raising

interest rates gradually. In this world with no lags our cautious

central banker would steadily raise interest rates until inflation

stopped increasing for a few quarters. Inflation would still be too

high, so they might raise interest rates once or twice again to get

inflation falling, and as it neared its target cut rates to get back

to the interest rate that kept inflation steady. [1]

Lags make the whole

exercise far more difficult. Imagine driving a car, where it took

several minutes before moving your foot on the accelerator had a

noticeable impact on the car’s speed. Furthermore when you did

notice an impact, you had little idea whether that was the full

impact or there was more to come from what you did several minutes

ago. This is the problem faced by those who set interest rates. Not

so easy.

With lags, together

with little experience and erratic movements in inflation, just

looking at inflation would be foolish. As interest rates largely

influence inflation by influencing demand, an interest rate setter

would want to look at what was happening to demand (for goods and

labour). In addition, they would search for evidence that allowed

them to distinguish between underlying and erratic movements in

inflation, by looking at things like wage growth, commodity prices,

mark-ups etc.

Understanding

current inflation

There are

essentially two stories you can tell about recent and current

inflation in these countries, as Martin

Sandbu notes. Both stories start with the commodity

price inflation induced by both the pandemic recovery and, for Europe

in particular, the war in Ukraine. In addition the recovery from the

pandemic led to various supply shortages.

The first story

notes that it was always wishful thinking that this initial burst of

inflation would have no second round consequences. Most obviously,

high energy prices would raise costs for most firms, and it would

take time for this to feed through to prices. In addition nominal

wages were bound to rise to some extent in an attempt to reduce the

implied fall in real wages, and many firms were bound to take the

opportunity presented by high inflation to raise their profit margins

(copy cat inflation). But just as the commodity price inflation was

temporary, so will be these second round effects. When headline

inflation falls as commodity prices stabilise or fall, so will wage

inflation and copy cat inflation. In this story, interest rate

setters need to be patient.

The second story is

rather different. For various (still uncertain) reasons, the

pandemic recovery has created excess demand in the labour market, and

perhaps also in the goods market. It is this, rather than or as well

as higher energy and food prices, that is causing wage inflation and

perhaps also higher profit margins. In this story underlying

inflation will not come down as commodity prices stabilise or fall,

but may go on increasing. Here interest rate setters need to keep

raising rates until they are sure they have done enough to eliminate

excess demand, and perhaps also to create a degree of excess supply

to get inflation back down to target.

Of course reality

could involve a combination of both stories. In last year’s post I

put this collection of countries into two groups. The US and UK

seemed to fit both the first and second story. The labour market was tight in the US because of a strong

pandemic recovery helped by fiscal expansion, and in the UK because

of a contraction in labour supply partly due to Brexit. In France and

Germany the first story alone seemed more likely, because the pandemic

recovery seemed fairly weak in terms of output (see below).

Evidence

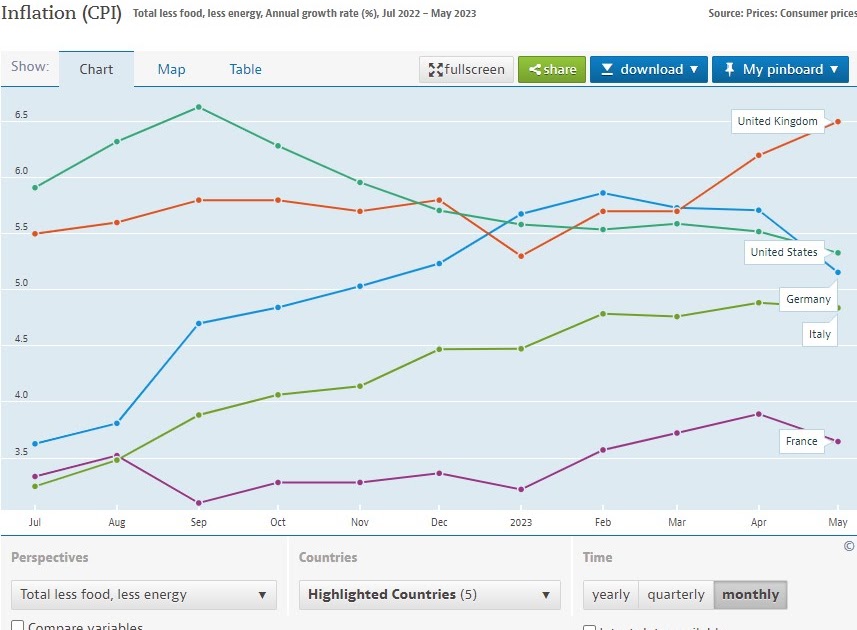

In my post two weeks

ago I included a chart of actual inflation in these five countries.

Here is a measure of core inflation from the OECD that excludes all

energy and food, but does not exclude the impact of (say) higher

energy prices on other parts of the index because energy is an

important cost.

Core inflation is

clearly falling in the US (green), and rising in the UK (red). In

Germany (light blue) core inflation having risen seems to have

stabilised, and the same may be true in France and Italy very

recently. The same measure for the EU as a whole (not shown) also

seems to have stabilised.

If there were no

lags (see above) this might suggest that in the US there is no need

to raise interest rates further (as inflation is falling), in the UK

interest rates do need to rise (as they did last month), while in the

Eurozone there might be a case for modest further tightening.

However, once you allow for lags, then the impact of the increases in

rates already seen has yet to come through, so the case for keeping

US rates stable is stronger, the case for raising UK rates less clear

(the latest MPC vote was split, with 2 out of 7 wanting to keep rates

unchanged) , and the case for raising rates in the EZ significantly

weaker. (The case against raising US rates increases further because

of the

contribution of housing, and falling wage inflation.)

As we noted at the

start, because of lags and temporary shocks to inflation it is

important to look at other evidence. A standard measure of excess

demand for the goods market is the output gap. According to the IMF,

their estimate for the output gap in 2023 is about 1% for the US

(positive implies excess demand, negative insufficient demand), zero

for Italy, -0.5% for the UK (and the EU area as a whole), and -1% for

Germany and France. In practice this output gap measure just tells

you what has been happening to output relative to some measure of

trend. Output compared to pre-pandemic levels is strong in the US,

has been pretty strong in Italy, has been quite weak in France, even

weaker in Germany and terrible in the UK (see below for more on

this).

I must admit that a

year ago this convinced me that interest rate increases were not

required in the Eurozone. However if we look at the labour market

today things are rather different. Ignoring the pandemic period,

unemployment has been falling steadily since 2015 in both Italy and

France, and for the Euro area as a whole it is lower than at any time

since 2000. In Germany, the US and UK unemployment seems to have

stabilised at historically low levels. This doesn’t suggest

insufficient demand in the labour market in the EZ. Unemployment data

is far from an ideal measure of excess demand in the labour market,

so the chart below plots another: employment divided by population,

taken from the latest IMF WEO (with 23/24 as forecasts).

Once again there is

no suggestion of insufficient demand in any of these five countries.

(The UK is the one exception, until you note how much the NHS crisis

and Brexit have reduced the numbers available for work since the

pandemic.)

This and other

labour market data suggests our second inflation story outlined in

the previous section may not just be true for the US and UK, but may

apply more generally. It is why there is so much focus on wage

inflation in trying to understand where inflation may be heading. Of

course a tight labour market does not necessarily imply interest

rates need to rise further. For example in the US both wage and price

inflation seem to be falling despite a reasonably strong labour

market, as our first inflation story suggested they might. The

Eurozone is six months to a year behind the US in the behaviour of

both price and wage inflation, but of course interest rates in the EZ

have not risen by as much as they have in the US.

Good, bad and

ugly pandemic recoveries

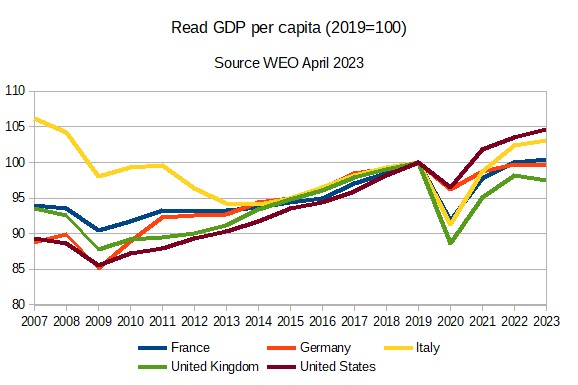

The chart below

looks at GDP per capita in these five countries, using the latest IMF

WEO for estimates for 2023.

Initially I will

focus on the recovery since the pandemic, so I have normalised all

series to 100 in that year. The US has had a good recovery, with GDP

per capita in 2023 expected to be five percent above pre-pandemic

levels. So too has Italy, which is forecast to do almost as well.

This is particularly good news given that pre-pandemic levels of GDP

per capita were below levels achieved 12 years earlier in Italy.

Germany and France

have had poor recoveries, with GDP per capita in 2023 expected to be

similar to 2019 levels. The UK is the ugly one of this group, with

GDP per capita still well below pre-pandemic levels, something I

noted in my post two weeks ago. Unlike a year ago, there is no reason

to think these differences are largely caused by excess demand or

supply, so it is the right time to raise the question of why there

has been such a sharp difference in the extent of bounce back from

Covid. To put the same point another way, why has technical progress

apparently stopped in Germany, France and the UK since 2019.

Part of the answer

may be that this reflects long standing differences between the US

and Europe. Here is a table illustrating this.

|

Real GDP per capita growth, |

2000/1980 |

2007/2000 |

2019/2007 |

2023/2019 |

|

France |

1.8 |

1.2 |

0.5 |

0.1 |

|

Germany |

1.8 |

1.4 |

1.0 |

-0.1 |

|

Italy |

1.9 |

0.7 |

-0.5 |

0.8 |

|

United Kingdom |

2.2 |

1.8 |

0.6 |

-0.7 |

|

United States |

2.3 |

1.5 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

Growth in GDP per

capita in the US has been significantly above that in Germany, France

or Italy since 1980. At least part of that is because Europeans have

chosen to take more of the proceeds of growth in

leisure. However this difference is nothing like the gap in growth

that has opened up since 2019. (I make no apology in repeating that

growth in the UK, unlike France or Germany, kept pace with the US

until 2007, but something must have happened after that date to

reverse that.)

I have no idea why

growth in the US since 2019 has been so much stronger than France or

Germany, but only a list of questions. Is the absence of a European

type furlough scheme in the US significant? Italy suggests otherwise,

but Italy may simply have been recovering from a terrible previous

decade. Does the large

increase in self-employment that occurred during the

pandemic in the US have any relevance? [1] Or are these differences

nothing to do with Covid, and instead do they just reflect the larger

impact in Europe of higher energy prices and potential shortages due

to the Ukraine war. If so, will falling energy prices reverse these

differences?

[1] If wage and

price setting was based on rational expectations the dynamics would

be rather different.

[2] Before

anti-lockdown nutters get too excited, the IMF expect GDP per capita

in Sweden to be similar in 2023 to 2019.