A reader writes in, asking:

“I’m not sure if you would consider a blog post or similar regarding cash (CD’s, Short Term Treasuries, Money Market, etc) but after reading and following your portfolio recommendations I’m curious if you have opinions on cash and how much to keep at any given time. I recognize all situations are different but you’ve always done a good job of laying out the options. My specific situation is: recently retired but my wife is working for another 2 years at which point we will both be retired.”

Firstly, I’m going to assume for the sake of this article that you already have a sufficient emergency fund in place or do not need an emergency fund. That is, we’re assuming that you already have a way to cover an unexpected major expense without incurring financial disaster. The question is simply: what part of the non-emergency-fund portfolio should be invested in cash?

And I’m also going to set aside the case of a “tactical” cash allocation (i.e., holding cash with the goal of investing it at just the right time after a downturn), because I’m not optimistic about the ability to do that in any useful way. Instead, I’m focusing on a static cash allocation (i.e., holding cash, with the intent of it being an ongoing part of the allocation).

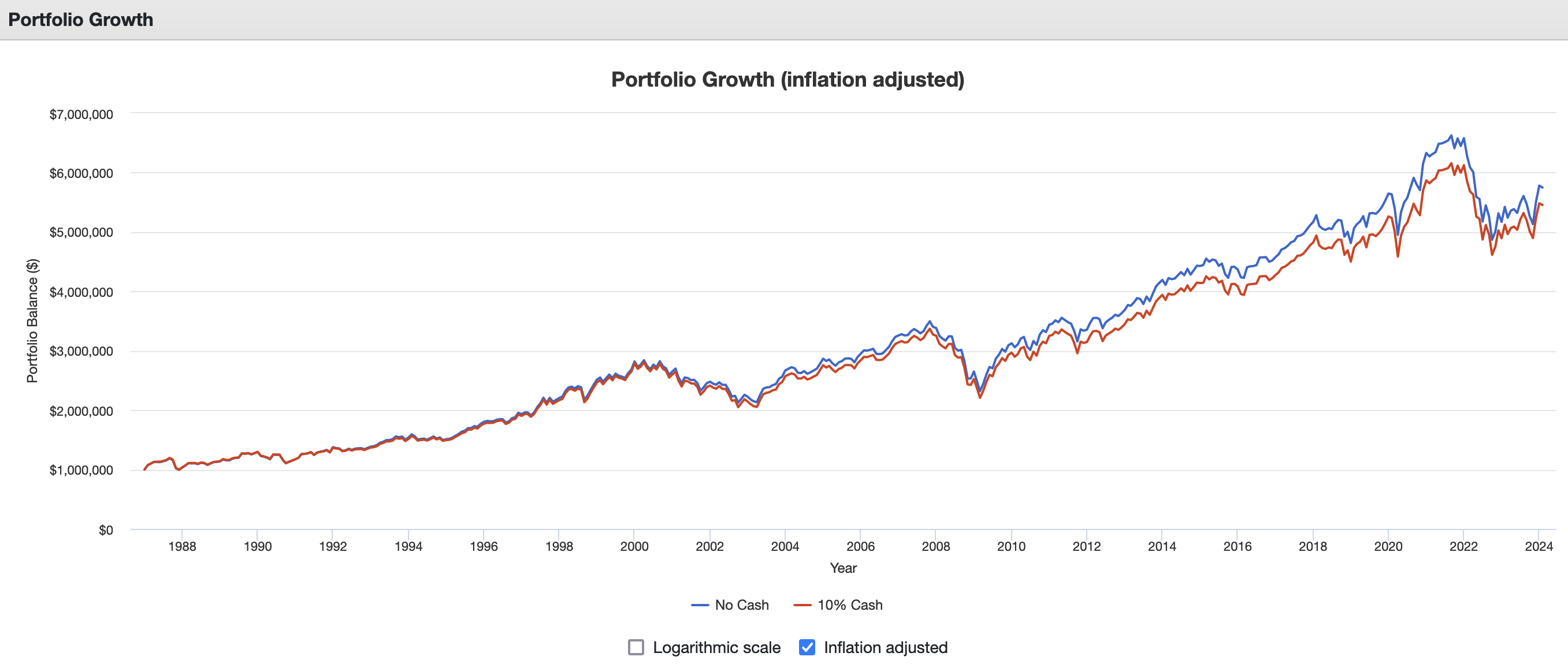

The following chart from PortfolioVisualizer shows a $1,000,000 initial portfolio balance, neither adding to nor spending from the portfolio over time. This is from January 1987 – January 2024. (January 1987 is the earliest date for which PortfolioVisualizer has “total US bond market” data.)

The blue line represents a portfolio of 40% total US stock market, 20% total international stock market, and 40% total US bond market. The red line represents of portfolio of 41% total US stock market, 20% total international stock market, 29% total US bond market, and 10% cash.* (The 1% increase in stock allocation is to keep the overall risk level similar.)

Here’s the PortfolioVisualizer link, in case you want to examine the numerical metrics or adjust any variables on your own.

To me, those look functionally the same.

Now let’s look at a portfolio from which we’re spending. The following chart from PortfolioVisualizer shows a $1,000,000 initial portfolio balance, using a “4%” rule type of spending strategy (i.e., spending $40,000 in the first year and then adjusting that spending upward with inflation). Again, this is from January 1987 – January 2024. And the asset allocations are the same as above. So this is a pretty significant cash allocation: 2.5 years worth of spending (10% of the portfolio, when spending 4% in the first year).

Here’s the PortfolioVisualizer link, in case you want to examine the numerical metrics or adjust any variables on your own.

Again, they’re very similar. And I think we can at least agree that, if the cash did make a meaningful difference, it was not in a useful direction.

And I get a similar set of conclusions whenever I run Monte Carlo simulations, whether via PortfolioVisualizer or RightCapital. Swapping out a chunk of the bonds for cash (and then adjusting the stock allocation upward a smidge, to make an apples-to-apples comparison) is…fine.

There’s nothing magical about cash. Whatever we can achieve by shifting a chunk of the portfolio from bonds into cash, we can probably achieve by just slightly bumping up the overall fixed-income allocation instead. This is just another case of “Asset Allocation Isn’t Magic.” There are lots of different asset allocations that will get you to a given level of risk and expected return, and any such allocation tends to be about as good as another.

Personally, I tend to opt for the simplest route (i.e., whichever allocation involves the fewest number of total funds or the least rebalancing).

But one relevant caveat is that, if cash specifically, relative to other types of fixed-income, helps you feel better about your portfolio (i.e., it makes bad days/months/years in the market feel less stressful because you know “I’ve got ___ years of cash, ready to tap into, if needed”) then that’s a compelling point in favor of a cash holding. But from a purely financial perspective, there doesn’t appear to be any specific need for a big cash allocation.

*PortfolioVisualizer uses 3-month Treasury Bills as the return for “cash.”

“A wonderful book that tells its readers, with simple logical explanations, our Boglehead Philosophy for successful investing.”

– Taylor Larimore, author of