The Budget was

predictable, and predictably boring. Hunt cut taxes, but the tax

burden is still rising because of the tax increases already

programmed in. Furthermore, he was only able to make the tax cuts he

did (i.e. reduce the extent of tax increases) because he had

previously pencilled in assumptions about public spending that were

fantastically low. You can either portray those assumptions as

Austerity 2.0 or just silly – I

did the latter here.

However, with (I

hope) the not silly assumption that this will be the last

Conservative budget [1] for a while, I thought it might be useful to look

back on the previous 14+ such events since 2010 to see if there are

any general lessons we can draw from them all. One in particular runs

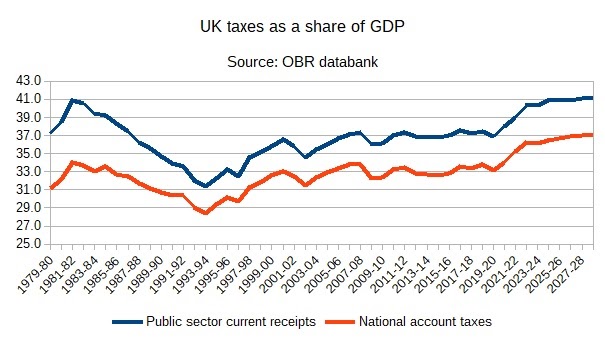

through most of them and really sticks out. From 2010 onwards

Conservative Chancellors have attempted to cut what they like to call the ‘tax burden’ by reducing the size of the

state without any major changes in what the state is meant to do, and as the chart below shows (which includes the impact of yesterday’s Budget) they have

completely failed to achieve this objective.

The professed aim of

Austerity 1.0 from 2010 onwards was to reduce the budget deficit, but

it quickly became clear that was not the only aim, because Osborne

started cutting taxes in his budgets as well as reducing spending.

(The initial VAT increase was deliberately designed to give the

impression it was all about the deficit.) Yet despite cuts to

corporation tax and personal tax thresholds, all Osborne could do

was to keep the tax share stable at around 33% of GDP.

Then came Brexit and

Boris Johnson. Johnson understood that trying to make Brexit work

while continuing to shrink the state was politically impossible, so

he undertook a partial and limited (in scope) reversal of Austerity

1.0 by raising spending on the NHS, schools and the police. This

would inevitably mean a large increase in taxes, undertaken by then

Chancellor Sunak for reasons he

clearly set out here. Even without the intervention of

Covid it is unlikely the additional spending would have been enough

to start bringing NHS waiting lists down, so the government got the

worst of all worlds in political terms: public services were

inadequately funded yet the tax share was going up significantly.

When Johnson was

thrown out of office, what little political sense he had brought on

the size of the state left too. It was replaced by fantasy and

deception, in that order. The fantasy was of course Truss, who had

bought the Laffer curve idea that all you needed to do to get more

revenue was to cut taxes because strong economic growth would surely

follow. Very few people believe this, in large part because it’s

not true. The deception is Jeremy Hunt, who is pretending he can cut

taxes by using make-believe numbers for future public spending

(Austerity 2.0).

Almost 15 years of

trying to reduce taxes, and complete failure. There are many reasons

why, but one for me stands out because it doomed the project to

shrink the state from the start. The chart below shows health

spending as a share of GDP in the UK, France, Germany and Italy since

1980.

Don’t worry about

the details, just note that all four series are trending upwards by

substantial amounts. There are many reasons for this trend, like

people living longer or discovering new ways to help them live

longer, but as yet we have not found anything to counteract health

absorbing a steadily increasing share of national income.

If governments try

to keep the health share constant (aka ‘protecting it’), as the chart clearly shows the UK

government did from 2010 until just before the pandemic, then the

quality of healthcare provided for most of the population will

steadily deteriorate. To avoid that deterioration, which is not

sustainable politically, you have to pay more of national income into

healthcare. If you have the NHS, that means a rising share of taxes

in GDP.

Decades ago this

trend rise in health spending as a share of GDP was offset by the

‘peace dividend’, with defence spending falling because of the

end of the cold war. Those days have long gone, with no obvious

replacement in terms of a major area of public spending where less and

less money is needed.

None of this was

unknown in 2010. The shrinking the state project was doomed from the

start, and anyone familiar with these numbers knew it was doomed from

the start. So why didn’t Conservative politicians realise this, and

why are they still in denial about it? I think in 2010 at least there

was a view among Conservatives that everything in the public sector

was inefficient, and the way to improve efficiency was to squeeze

resources or introduce market mechanisms. [2] Again there were

international comparisons that suggested this wasn’t true, for the

NHS at least, but the story fitted too easily with a neoliberal

viewpoint.

However you have to

ask if any Conservative who had realised the futility of trying to

shrink the state would have been successful as politicians? It was

and continues to be a message that Conservative members, press

barons or donors don’t want to hear. Look at how Sunak’s position has

changed from one recognising realities as Chancellor to a Prime

Minister who has to pretend he can get something for nothing. The way

politics is done in the media doesn’t help either, where basic

numerical facts like an international trend rise in the share of

health spending in GDP seems too much for many political journalists

to remember.

So the chances of

the Conservatives giving up their obsession with tax cuts is close to

zero. In addition the media will remain constantly surprised that UK

tax shares are steadily rising. This is unfortunate, because in

trying to do the impossible (reduce the tax share) the Conservative

party has done a great deal of harm. Obvious harm to the public

services, but also to the economy.

Austerity 1.0 is a key reason why

the UK’s recovery from the Global Financial Crisis recession was so

weak, and austerity also

played an important part in influencing the Brexit referendum result. The

damage caused by Truss we all know, while the game played by

Hunt/Sunak is in danger of preventing Labour doing enough when they

gain power. The dire state of the NHS is also directly influencing the economy. As the OBR notes, the number of inactive working age adults has increased substantially since the pandemic, with many citing long-term illness. The OBR now expects no recovery in labour force participation over the next five years, making the UK quite different from other countries where post-pandemic participation rates have recovered. This seems quite consistent with the continuing squeeze on public sector spending. For more details on how poor health has a negative influence on the economy as well as wellbeing, see the reports from the IPPR’s Commission on Health and Prosperity, and Bob Hawkings here.

While there will always be a debate about whether high or

low tax countries grow faster, the UK’s experience over the last 14 years show that trying to cut taxes by shrinking the state when it

is impossible to do so is very damaging indeed. Unfortunately neither the Conservative party nor many political commentators in the media appear willing to recognise the damage these attempts have done to both social wellbeing and the UK economy.

[1] I fear there will be one more Autumn Statement before the election, and because that will involve another year of nonsense public spending assumptions, it will give the government room within its fiscal rules for further tax cuts.

[2] What they also did was starve the NHS of investment, which was bound to decrease efficiency, and privatize increasing amounts of its provision, which reduced the quality of provision.