The goal of my investing from the beginning has been to build up my portfolio to the point where portfolio distributions can cover my expenses. That would provide the freedom to own my time and allocate it to my best interests, rather than be dependent on the whims of others (e.g. employers).

Being able to support yourself and your family with investments is something that happens after many years of patient and regular investing. This is an exercise in deferred gratification, and trying to take care of your future self. Very few are able to accomplish that, for a variety of reasons.

I like the idea of Generational Wealth. This is where you are able to set-up an investment portfolio that can provide for future generations of your own family. It could also mean providing for future generations of mankind in general, if you decide to leave those funds for a charitable cause.

I have played with compound tables of returns for many years. I have always been blown away from the power of compounding at a decent rate of return over a long period of time.

Given the fact that U.S. Equities have managed to generate annualized returns of about 10%/year over many decades and about two centuries (on average), I have often wondered why there not more families with Generational Wealth derived from the stock market.

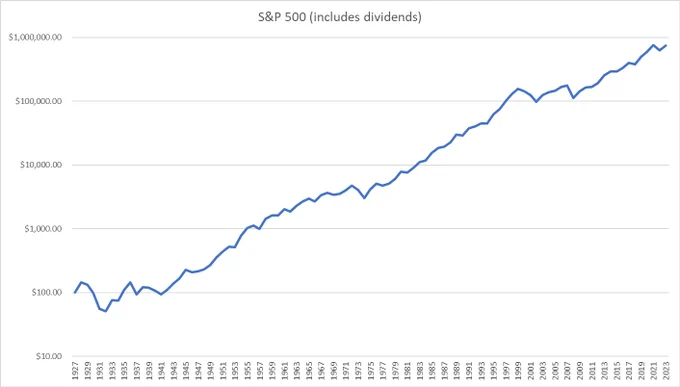

In a way, my thought process is about investing a certain amount today, and compounding it over a long period of time to get to a certain amount of money. I tested this using actual data available for US equities between 1927 and 2023. I then thought about the obstacles to that activity, and why this hasn’t happened.

There are various lessons when you think backwards from it, which could be helpful in understanding the obstacles to compounding, family relations, and ensuring wealth stays in the family for generations. There’s certain qualitative aspects of it all, which make it a fascinating thought exercise. Creating structures, processes, lifestyles to alleviate those concerns is definitely something to think about.

Anyway, let’s imagine a family which:

1. Invested $10,000 in S&P 500 at the end of 1927

2. Turned the DRIP on

3. Let the investment alone until today

They would have a portfolio worth $74,200,000 today.

That’s a fascinating testament to the power of compounding. For each $100 invested at the end of 1927, that family ends up with $742,000. I used S&P 500 for a proxy for US Equity returns. It yields 1.50% today, so that trust fund can generate roughly $11,300 in annual dividend income. At a 3% yield, it can generate $22,600 in annual dividend income.

Knowing this information, I often wonder why there aren’t many millionaires and billionaires even. All it took is a small amount of money to be invested, and then left uninterrupted for decades.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of obstacles to this type of compounding.

1. You need to have an amount that is saved and invested in the first place. If you are unable to save anything, you can’t invest and enjoy the power of compounding.

For context, that $100 in 1927 has the same purchasing power of roughly $17,500. A daily wage at Ford Motor Company was at about $5. A Ford Model T cost about $300. I would venture that a lot of families may have had $100 to their name in 1927, at least in the US. Savings rates were probably higher back then than what they are today as well. However, only a small portion of folks in the US invested in the stock market in the first place. Most saw it as a place for speculation, rather than long-term investment.

Of course, you don’t need to invest $100 or $10,000 at once. Probably the best way to invest is through a regular program, where one saves a certain portion of paycheck and allocates it into productive assets.

You may argue that not many families had $10,000 in 1927. However, I would argue back that the number of almost billionaires today is smaller than the number of people who had $10,000 in 1927.

2. Your family needs to be smart about money for several generations and not waste that money.

It’s very hard to save and invest and defer gratification for yourself. It’s even harder to accomplish that by instilling those values to future offspring. One individual may build the wealth, and the second may grow up in a phase where wealth was not abundant yet. Hence, they may still have the habits of frugality, thrift and industry that build and maintain wealth. The third and fourth generations however may have different viewpoints, because they could have been born in relative wealth. The phrase “shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations” comes to mind when discussing this.

3. Your family would just let money compound for several decades from several generations without taking any distributions from it is a low probability event. It also means that they did not panic and sell during Depressions, Wars, Recessions, etc

Buying a holding a portfolio of US Stocks is not easy to do through the ups and downs of the US and Global Economies. There is this instinct to try and protect what you have by selling during a bear market, in order to “stop the bleeding”. This is typically when the bear market is close to being over too, thus missing out on the potential recovery. Trying to time the markets is definitely a costly endeavor.

If that family was living off the distributions however, a $100 investment in 1927 would have been turned to $26,000 by today. A $10,000 investment at the end of 1927 would have turned to $2.60 Million.

4. You need to do proper tax planning and asset placement throughout that time.

Income was taxable at various tax brackets and tax rates, and taxes on dividends and capital gains had varied. We didn’t always have retirement accounts, but we had other tax loopholes to leverage and lower taxes. Even a successful tax efficient strategy may incur cost in the form of professional advisor expenses.

5. Speaking of taxes, you also need to be aware of the estate tax, and ensure you don’t get hit by it.

The purpose of the estate tax is to avoid having large amounts of money simply compound for decades, creating dynastic generational wealth. Even if you were to use a foundation, there is a requirement to spend 5% of assets each year on activities, which reduces corpus.

6. It is very hard to find an investment that would compound at a steady clip for decades.

It would have been possible to replicate results of Dow Jones Industrials Average companies, but the costs of doing that would have detracted from returns. S&P 500 was introduced in 1957, and the data before that is from previous indices existing, which had less than 500 components. It was hard to invest in just S&P 500 until 1976. Long story short, it was hard to buy S&P 500. Someone could have done better or worse because they built their portfolios on their own, not knowing what we know today. They would have likely also owned other assets such as bonds, real estate, etc.

7. This also assumes that the investment is done is a low cost manner.

I mentioned this above, but I also wanted to mention it here again. You could have paid a ton in taxes on dividends and capital gains and potentially estate tax. You could have hired a tax professional and/or a financial advisor to manage the funds. That could cost money each year however, further reducing the end dollars at stake. They could also keep the family in check, and not allow them to just spend everything. Or they may end up providing questionable advice on investments or do a poor job in planning. If they delivered more value than what they cost however, perhaps that trade-off may have been worth it. If they don’t, then it may not have been worth it.

8. There is a certain element of survivorship bias at work here

It’s hard to find a family that had a certain amount of money in 1927, let alone let it compound for so long at a low cost and high rate of success and keep it. It’s also probable that this family disintegrates on its own if it doesn’t produce offspring for example, or tragedy struck them.

There have been other markets and countries where rich people lost everything, due to nationalizations, upheavals, etc. There are other markets where equities had dismal returns, even if they survived.

Conclusion:

What is the purpose of this article?

Long story short, the power of compounding is powerful. But you also have many obstacles on the way to compounding for long periods of time and obtaining generational wealth for your family.

If you identify those obstacles in advance, you can design a plan to remediate them as much as possible.

This includes selecting investments with staying power, staying invested through the ups and downs, and having a diversified portfolio. It also involves ensuring that you pay the least amount in taxes and investment costs over time. In terms of stewardship, you need to work in instilling the right values in the next generations after you, including a way to instill those values to generations that you may never meet. While cost is important consideration, it may be beneficial to employ an investment professional or a team of professionals to help navigate these treacherous waters. They can help with items as investment management, tax and estate planning, and even basic financial management for future generations.