Steep rises in the prices of sugar and cocoa are set to hit sweet treat lovers’ wallets as extreme weather conditions hinder production, even as broader measures of food inflation ease off.

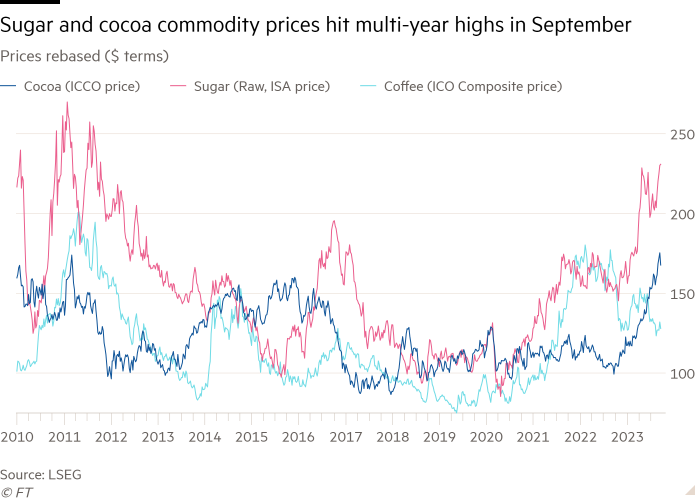

This month sugar prices hit their highest level in 12 years and cocoa futures reached a four-decade high, in a move which analysts said was likely to feed through into higher prices for hot drinks and confectionery.

Chocolate manufacturers and processors have been “praying for prices to drop all year and they just haven’t”, said Andrew Moriarty, price reporting manager at Mintec. Instead, they are set to rise further, he said: “We can expect costs to start being passed on to consumers soon.”

Consumers can also expect further “shrinkflation” in product size and substitution of ingredients to cut costs, he added.

The price rises have been driven by supply fears as the El Niño sea temperature phenomenon, coupled with rising temperatures resulting from climate change, bring extreme heat to parts of Asia and diminished rainfall to West Africa, threatening yields of sugar, cocoa and coffee.

“What’s really driving these price rises is the prospect of a [supply] deficit in 2023-24,” said John Stansfield, senior sugar analyst at DNEXT.

Food manufacturers have signalled they will pass on the latest cost increases. François-Xavier Roger, chief financial officer at the world’s largest food manufacturer Nestlé, told investors this month the company did not plan to raise prices much higher except “on a selective basis for some categories where we still see some input cost inflation, like for cocoa, for sugar, for robusta, for coffee”.

In the UK confectionery prices rose by 15 per cent in the year to June, while in the US candy prices jumped 9.4 per cent in the year to August.

Despite this, sales have proved resilient. Analysts said that although shoppers have cut back other spending, they tend to regard treats such as confectionery as affordable luxuries.

That has proved a boon for manufacturers. Cadbury maker Mondelez and Hershey have both raised their profit forecasts for the year.

“The advantage of cocoa and confectionery is it’s a very resilient market,” said Bruno Monteyne, analyst at Bernstein. “People keep eating chocolate.”

Sugar prices rose after unseasonably dry weather in the southern states of Karnataka and Maharashtra hit production in India, the world’s largest sugar producer. Analysts forecast a 4mn-tonne production shortfall in the 2023-24 season from the 32.8mn tonnes produced a year earlier.

India capped exports at 6.1mn tonnes for the 2022-23 season, down from 11mn the year before, and is considering a total export ban from October, which would further crimp supplies, said Stansfield.

Looming elections in five states, and national elections next year, make export curbs more likely, he added, given that “sugar is extremely political in India”.

Sugar prices have eased slightly from their peak earlier this month after a bumper corn crop in Brazil prompted ethanol producers to switch to the grain, freeing up sugar supplies.

Cocoa prices have more direct impact on consumer products than sugar, however, said Andy Duff, global sugar strategist at Rabobank.

Ivory Coast, which produces 70 per cent of the world’s cocoa beans, expects a “mediocre harvest”, said Yves Brahima Koné, head of the country’s Coffee and Cocoa Council, blaming “too much rain and not enough sunshine”.

Analysts expect the west African country’s output for the coming season to be down by about 15 per cent.

With prices already running high for the past 18 months, chocolate makers have limited their purchases, said Moriarty.

“The entire industry is running short on cover,” he said, adding that some manufacturers only have supplies to last until the end of the year. As a result, buyers are now being forced to take the hit and purchase at higher prices, said Moriarty.

As well as increasing prices, manufacturers also shrink products to mitigate rising costs, said Paul Joules, cocoa analyst at Rabobank.

French supermarket chain Carrefour this month slapped stickers on products whose size had been reduced, including Unilever’s Viennetta ice-cream and Lindt chocolate, warning consumers of “shrinkflation”.

Chocolate manufacturers also offset rising cocoa prices by adjusting other ingredients to cut costs, for instance by increasing palm oil content or using cheap powdered milk instead of anhydrous milk fat, said Joules.

Erratic weather in recent months has also knocked production of robusta coffee in Vietnam and Indonesia, the world’s second- and third-largest producers. If El Niño creates a prolonged dry spell, this could further reduce yields.

This is bad news for espresso drinkers, especially in Italy, where robusta beans dominate. Drinkers of instant coffee may face a bigger hit, said Moriarty. The product uses robusta and is energy-intensive to produce, so is affected by high energy prices.

While chocolate and coffee seem like food basket luxuries, the rising costs for underlying commodities point to the fragility of the global food system, said Professor Tim Benton, food security expert at Chatham House.

Surging rice prices, which have reached their highest levels since 2008 as El Niño and poor weather threatened yields, could drive up costs of other commodities and spur Asian inflation, HSBC analysts warned this month.

More aggressive broad-based food inflation could easily return, said Benton. Agricultural commodity markets were complacent about risks linked with El Niño, he added, “but we’ve never had an El Niño in a world that is as hot as it is today”.