The rule of thumb

journalists use to define a recession, two quarters of negative GDP

growth, is unhelpful in many ways. If the economy grows by 0.1%, the

headline is ‘UK avoids recession’, but if it grows by -0.1% in

two consecutive quarters, the headline is ‘UK enters recession’.

Yet the difference between those two, 0.2% of GDP, is well within the

measurement errors typical associated with GDP growth. From an

economic point of view there is no material difference between 0.1%

growth and -0.1% growth, so calling the later a recession but the

former not is rediculous.

Another problem with

this way of defining a recession is that it makes no reference to

trend growth. If the economy typically grows by 3%, then zero growth

is a big difference (3% less than normal). However if trend growth is

more like 1%, then zero growth is not such a big deal (just 1% less

than normal). This can lead to serious misreporting when talking

about a recovery from a recession. For example some have claimed that

because GDP started growing in 1982 after the 1980/1 recession the

famous letter from 364 economists was wrong. As I

noted here, growth in 1982 was around the trend rate.

The recovery, in the sense of getting back to trend, only really

started in 1983.

One final problem

with the ‘official’ definition of recession is that it refers to

GDP, rather than GDP per head. The latter is far more relevant in

almost every way.

|

UK Quarterly growth |

Real GDP |

Real GDP per head |

|

2022Q1 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

|

2022Q2 |

0.1 |

-0.2 |

|

2022Q3 |

-0.1 |

-0.2 |

|

2022Q4 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

|

2023Q1 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

|

2023Q2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

|

2023Q3 |

0.0 |

-0.1 |

As the table above

shows (source),

if we used GDP per head in the official definition of recession, then

we had a recession in 2022, and we could be heading for a second

recession in the second half of this year. Again this shows the

nonsense of being so literal about defining a recession.

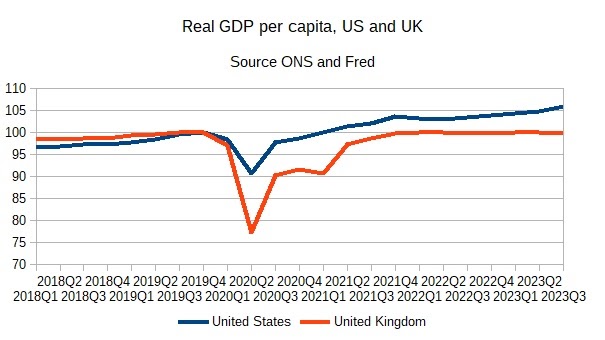

A much better way of

describing 2022 and (so far) in 2023 is that the economy has

flatlined. It is tempting to ascribe this period of very weak growth

as a consequence of rising interest rates to combat high inflation.

Growth in the major EU economies has also been weak over the last two

years. However one important counterexample should make us question

this simple explanation. As the graph below shows, growth in the US

has been much stronger.

Martin

Sandbu shows a similar graph comparing US GDP to EU

GDP. While UK GDP per capita remains at similar levels to just before

the pandemic, US GDP per capita is almost 6% higher. The UK recorded

a slight fall in GDP per capita in 2023Q3, but US GDP per capita

increased by over 1%!

As Martin notes,

this is not because US GDP per capita growth is always higher than in

Europe. Equally, as

I showed here, UK growth in GDP per capita was at

least as strong as the US before the financial crisis and austerity.

Something has been happening in the US since the pandemic that has

not been happening in the UK and EU.

As with any puzzle

there are many possible answers, and not enough evidence to know for

sure which is correct. One answer is that the energy price shock hit

Europe much harder than the US, because gas markets are more local

than the oil market and gas supplies were restricted by Russia’s

invasion of Ukraine. If that was the case, then in 2023 we should be

seeing some rebound in Europe relative to the US as gas prices came

down, but as yet there is no sign of this. So this is only a partial

explanation.

The argument I have

made before, and Martin also makes, is that US fiscal policy has been

much more expansionary since the worst of the pandemic than in

Europe. The details are discussed at length in

that previous post and in Martin’s

article so I will not repeat them here, except to say

that they involve a combination of the timing of fiscal stimulus and

directing that stimulus to those who will spend more of it. Instead I

want to broaden this out to make a much more general point.

One feature of

Biden’s tenure as President is that policy has not put the budget

deficit or debt at the centre of fiscal decisions. This is in

contrast to Europe, where in both the EU and UK constraints on debt

or deficits imposed by politicians always seem to bite, and also in

contrast to previous Democratic administrations which have ‘worried

about the deficit’ to varying degrees. In my view the strength of

the US economy coming out of the pandemic owes a great deal to this

difference, and this holds important lessons for European

policymakers who remain obsessed with and constrained by deficit or

debt targets.

What do I mean by

deficit obsession? After all, I have consistently

argued that setting fiscal policy over the medium term

to follow the golden rule (matching day to day spending to taxes)

during normal times is a good objective. Deficit obsession, by

contrast, implicitly views public debt as always a bad thing, erects

totally arbitrary targets to reduce that debt, and allows this to

dictate policy at almost all times, which invariably means

underinvestment in public services and infrastructure.

Deficit and debt

obsession matters most after a severe economic downturn,

caused for example by a financial crisis or a pandemic. After the

Global Financial Crisis the key mistake was not the absence of fiscal

support during the period when output was falling, but during the

period after that when we would normally expect a recovery from that

recession. This was because in the US and UK, Democrats and Labour

were in power. However even in Europe there was some fiscal support

during the worst of the recession. During the worst of the pandemic

all governments offered considerable fiscal support. It is after the

immediate crisis that mistakes were made. It is as if policymakers

were prepared to suspend their deficit obsession while output was

falling, but once output stopped

falling that suspension ended. In a way, they were also being misled by the ‘official definition’ of a recession.

We know from the

1930s depression that the level of output after a crisis does not

always bounce back to its pre-crisis trend. Thanks to Keynes we also

know why. If consumers and firms think that perhaps such a bounce

back will not occur, it will not, because consumption and investment

will remain depressed. In the 1930s unemployment stayed high, yet

wages and prices stopped falling. It needed a fiscal stimulus, in the

form of the New Deal or a war, to reduce unemployment. Unemployment

did fall after the Global Financial Crisis, but output did not return

to its pre-crisis trend.

We are seeing the

same pattern after the pandemic. We had a V-shaped recession, but

output in Europe has not returned to its pre-pandemic trend, because

in the EU and in the UK policymakers have returned to imposing

deficit or debt targets that leave no room for encouraging a full

recovery. The one exception is the US, and it is there that output

has returned to something like its pre-pandemic trend.

In the EU and UK

policy makers typically view the increase in debt during the crisis

as an unfortunate outcome, rather than a beneficial means of

softening the impact of the crisis. As a result, as soon as the

crisis is over they try to reduce the new higher level of debt

through fiscal consolidation rather than stimulating the recovery. We

know that is unlikely to work on its own terms (fiscal

consolidations when the output gap is negative tend to increase debt

to GDP) , and it also risks permanently damaging average incomes.

I have been making

this argument consistently over the decade I have been writing this

blog, but for most of this time all the major economies have been

afflicted by deficit obsession so I have been unable to point to a

current example of how things could be done much better. Thanks to

President Biden and Democrat policymakers, now I can, and the results

speak for themselves.

.