By Lucinda Elliott and Natalia A. Ramos Miranda

SANTIAGO (Reuters) – Chileans on Sunday will vote in a referendum on a new constitution that seeks to replace its dictatorship-era text.

The push to rewrite the constitution that dates back to the 1973-1990 rule of General Augusto Pinochet was born out of fiery protests four years ago sparked in part by deep inequality that many blamed on that framework.

The irony? This rewrite is more conservative than what it is replacing.

The mandatory plebiscite is the country’s second attempt at drafting a new charter. The first attempt was written by a body elected by popular vote and dominated by left-wing voices. It granted far-reaching environmental protections and guaranteed a wide slate of social rights. But for many Chileans it was too radical and it was rejected in September 2022 by voters.

Chileans then elected an assembly, this time dominated by the right, to draft another version that will be put to a vote on Dec. 17.

In the balance is whether to adopt the proposed 216-article constitution that places private property rights and strict rules around immigration and abortion at its center, or stick to the current version.

“It is a text that consolidates the market-friendly economic model instead of weakening it,” Chilean political scientist Patricio Navia said of the draft. “Pensions cannot be nationalized, there are strict rules on property,” he said.

Proponents at the start of the process hoped a new constitution would help usher in an era of unity in Chile, following a wave of public anger that ended in mass demonstrations in 2019 over rising inequality and the poor state of public services.

But priorities have shifted for many Chileans amid a sharp economic slowdown, constitution fatigue and discontent over rising crime.

“It was four wasted years, we have ended up in the same place we began,” Navia said, adding that one “silver lining” was that Chileans have indicated that they favor the current market-friendly economic model – they just want it to work better.

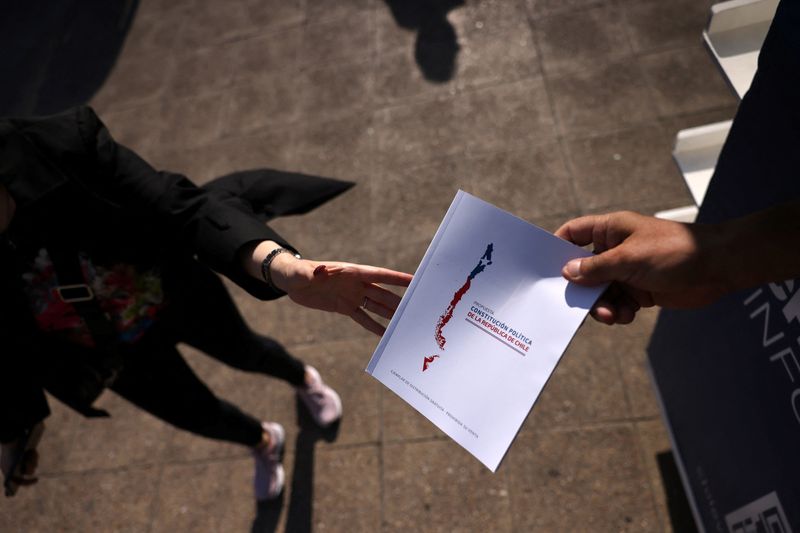

Cecilia Ibanez, 62, said she no longer knew what to decide while being handed a free copy of the proposed constitution, distributed ahead of the vote in Santiago. “For me the three important factors are those that were fought over in the ‘outbreak’: retirement, health and education,” she said of the 2019 protesters’ demands.

For Jose Luiz Pizarro, a 74-year-old, the biggest issues in Chile today are crime and security rather than the social policy concerns that first drove the rewriting process.

“The constitution won’t solve those problems right now, but over time, yes, this will be solved with laws,” Pizarro said.

Claudia Heiss, a researcher and political scientist at the University of Chile, said that issues like crime, migration and economic stability have taken over public debate and the end goal that sparked the effort to change the constitution has been lost.

If the new constitution is approved, it “won’t resolve the problems associated with the social unrest,” Heiss said.

The campaigns during the second rewrite have also been largely muted compared to the concerts, social media campaigns and public events that marked last year’s build-up.

In part, that is because there is less of a clear direction change with the new rewrite, said Heiss.

“It’s keeping the constitution of 1980 or approving a constitution that basically reinforces what’s already there,” Heiss said.

Support for the new proposal has been trailing in opinion polls but has gained ground in recent weeks. Pollster Cadem’s last numbers showed that 38% would approve the new constitution, a six-point bump from its previous poll in mid-November, while those against fell three points to 46%.

Leftist President Gabriel Boric had championed the reform process, but has distanced himself from the current rewrite which is dominated by the right-wing Republican Party, led by Jose Antonio Kast.

Kast lost the 2021 presidential election to Boric and many see Sunday’s vote as a bellwether of the country’s political climate.

“If it passes, Boric has no purpose, he will be a lame duck,” said Navia. “If the constitution does not pass, Boric still has a chance and a purpose.”

Should it fail to pass, the president has said he would not push for a third rewrite, but could instead try to amend the current text to include popular proposals like expanding reproductive and environmental rights. The 1980 version has already been amended a number of times over the decades.

Diego Rozas, a 24-year-old accountant from Santiago, said he was still interested in the process, but was fed up with Chile’s political extremes.

“We Chileans are tired of politicians on one side and the other. We have to look for middle ground to make a decision,” Rozas said.

About 15.4 million people are eligible to vote in the mandatory plebiscite starting at 8 a.m. local time (1100 GMT) on Sunday. Results are expected by 8 p.m. local time.

(Reporting by Lucinda Elliott and Natalia Ramos; Editing by Alexander Villegas and Rosalba O’Brien)