This article was reported in partnership with Type Investigations.

On June 14, 2016, several agents with Immigration and Customs Enforcement loaded a van with 2,000 pounds of marijuana, drove it to a busy shopping center in Chula Vista, California, and parked it outside of a Starbucks. There, an undercover agent, Special Agent Ronaldo Gonzalez, had a plan to make a sale.

When the intended buyers, members of a known drug-trafficking organization, fell through, a contact helped him find another last-minute option, according to court documents. First, the contact showed up with two unknown potential buyers, whom Gonzalez later described as “kids,” then two more young people appeared.

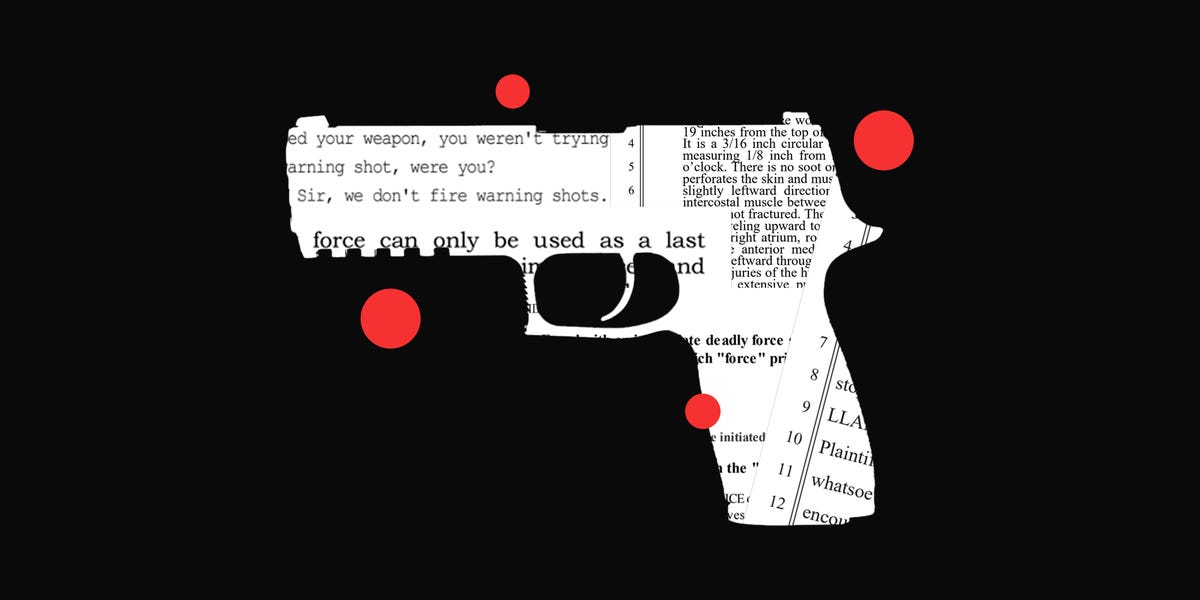

As Gonzalez opened the van’s door to get out some product, he heard a commotion and spun around. He later told the Chula Vista police that he saw one of the young people, later identified as Fernando Llanez, 22, aiming a black-and-yellow weapon his way. Within 10 seconds Gonzalez had shot Llanez four times, killing him.

The fourth and fatal bullet, according to an excerpt of the autopsy cited in the complaint, entered Llanez’s back, after he had already collapsed, face down, on the asphalt, and lodged in his tongue.

Llanez’s weapon turned out to be a Taser.

US District Court for the Southern District of California

“They were just a bunch of kids,” said Jorge Hernandez, an attorney who represented the Llanez family. “This guy wasn’t in uniform. The kid that got shot never knew he was a cop. Never flashed a badge. Never disclosed. Nothing.”

The young people Gonzalez approached weren’t the target of the sting operation, according to a civil complaint Hernandez later filed. Once a situation becomes unpredictable, Hernandez said, agents typically call a sting off. But in this case, he said, “they never called it, so it escalated.”

So much could have gone differently that day in Chula Vista. Gonzalez could have identified himself as a law-enforcement officer. Or he could have tried to de-escalate the situation. But the Llanez family never learned whether Gonzalez had followed ICE training protocols, because the way ICE agents are trained has been largely hidden from the public.

Miguel Alvarez, an ICE spokesperson, said the agency does not comment on investigations or litigation.

US District Court for the Southern District of California

A joint investigation by Business Insider, The Trace, and Type Investigations identified Llanez as one of 23 people killed by ICE officers from 2015 to 2021, with dozens more injured.

The Department of Homeland Security requires its member agencies, including ICE, to minimize the risk of injury and risk to the public, and its amended 2023 use-of-force policy requires officers to be proficient in de-escalation tactics. But ICE has never explained publicly how it prepares agents before sending them in the field.

For years, civil-rights groups have sought to obtain, with limited success, complete ICE training documents to understand how that training affects use of force by agents in the field. Business Insider and Type Investigations have now obtained hundreds of pages of previously unreported ICE training materials, including PowerPoint presentations, lesson plans, quizzes and answer sheets, and transcripts of multimedia presentations. None of the training documents we obtained address how to de-escalate tense or dangerous situations and avoid the use of force.

Though the materials may have since been updated — they are dated from 2006 to 2011, and ICE revised its training program in 2015 and 2022 — and do not represent a complete training curriculum, they offer the first in-depth look at training that shaped a generation of ICE agents, including Gonzalez, who was hired in 2006.

We couldn’t find any guidance requiring immigration agents to identify themselves to suspects before using deadly force. And they also appear to place an emphasis on teaching ICE agents how to justify the use of force.

Ivón Padilla-Rodríguez, a professor of history at the University of Illinois Chicago who studies child migration and labor trafficking, said that the public has a stake in how immigration agents are trained. “They operate with a lot of impunity and a lot of discretion,” she said, “and that ends up in the death of immigrants.”

Alvarez, the ICE spokesperson, said by email that the agency’s officers “are committed to protecting the homeland with the utmost integrity” and its leaders “reinforce standards of ethical and responsible conduct to further build and maintain public trust.”

‘Deadly force can be initiated immediately’

Most ICE officers are trained at sites in Charleston, South Carolina, or Glynco, Georgia, run by the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers, a division of the Department of Homeland Security. There, FLETC offers aspiring agents basic law-enforcement training, which includes use-of-force training, from how to respond to threats to writing up incident reports; firearms training such as proper handgun and rifle use, shooting positions, and live-fire cover; and legal training, covering rules of evidence, officer liability, and courtroom testimony.

Among the most important lessons ICE agents receive is when and how to use deadly force.

We found no lessons teaching strategies for de-escalation. To the contrary, some lessons appeared to encourage the agents to use force quickly and decisively.

One publicly available use-of-force training document, from 2016, said it was a myth that use of deadly force could be used only as a last resort, regardless of agency policy. “Objective reasonableness is the law; not policy,” the document reads. “Using the minimal force, exhausting all lesser means of force, or always giving a warning could create an unnecessary risk for the officer.”

Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers

This is exactly what attorneys for Special Agent Gonzalez argued in court, when the Llanez family filed suit. “It is well settled that an officer’s use of deadly force is reasonable where he had probable cause to believe that the suspect posed an immediate and serious threat to his safety or the safety of others,” the motion to dismiss reads. It was an argument that persuaded a federal judge, who dismissed the case. (Gonzalez didn’t face criminal charges either, Hernandez, the family’s attorney, said, though Alvarez, the ICE spokesperson, declined to confirm that. Gonzalez’s lawyers at the Department of Justice declined to comment.)

Citizens have the right to bear arms, the lesson goes on to say, but if an officer orders someone to put down their weapon and that order isn’t followed, officers “are not required to wait for someone to take a bead on them.”

Among the documents we obtained is a lengthy set of quizzes, including more than 100 multiple-choice questions, with answer keys. Only one set of five questions deals with use of force. One of the questions asks which steps an officer must take before initiating deadly force; the answer is “None, deadly force can be initiated immediately.”

Alvarez, the ICE spokesperson, disputed these findings, saying officers and agents are “trained to only use force as a last resort when objectively reasonable and necessary, and to leverage de-escalation tactics.” He said ICE officers are regularly retrained, and any violation of policy is investigated thoroughly. ICE’s basic training program, he said, added more emphasis on de-escalation in 2022.

FLETC did not respond to detailed queries about how ICE agents are trained.

Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers

As early as 2006, just three years after DHS was established, a basic-training instructor named John Bostain wrote in the FLETC trade journal that officers should be “proactive rather than reactive in their application of force.”

Jim Trainum, who worked with the Metropolitan Police Department in Washington, DC, for 27 years and now offers criminal-case review, including on cases involving the use of force by federal officers, says that emphasis is not uncommon in law enforcement. “A lot of the training gives you excuses and justification for using force,” he said.

A 2016 shooting in Laurel, Mississippi, shows how this kind of training can play out in the field, and in the aftermath.

During a traffic stop, the local police called ICE agents to assist with translation. But one of the agents, Phillip Causey, ended up shooting a man, Gabino Ramos Hernandez, who wasn’t even the subject of the stop. Ramos, an unauthorized immigrant, bolted once the ICE agents arrived, but then turned around to turn himself in, holding one hand up while he held up his pants with the other.

Causey told the court he opened fire because he suspected Ramos was reaching into his pants to retrieve a weapon.

US District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi

Four years later, on a humid, 91-degree summer day, Ramos’ lawyer, Timothy Cerniglia, met Causey at a federal courthouse for his deposition.

“At the time that you discharged your weapon, you weren’t trying to fire a warning shot, were you?” Cerniglia asked.

“Sir, we don’t fire warning shots,” Causey replied.

“You were shooting to kill,” Cerniglia said.

“That’s what we’re taught to do,” Causey said.

A judge dismissed the case Cerniglia brought for failing to show that Causey had violated Ramos’ rights; the ruling is now being appealed. Though the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation, which investigated the shooting, brought charges to a grand jury, the jury chose not to indict. None of Causey’s lawyers at the Department of Justice responded to requests for comment.

Alvarez, the ICE spokesperson, said ICE officers and agents are not trained to shoot to kill, but are trained to use deadly force only to stop whatever threatening behavior they face.

Evading accountability

The training documents we obtained appeared to focus more attention on evading accountability for use-of-force incidents than on how to avoid firing a weapon in the first place. They detail the factors courts consider when deciding whether use of force by a law-enforcement officer is justified and explain how agents should describe what they do in the field to survive legal scrutiny.

“Good fact articulation helps the court make an objective decision,” one publicly available lesson reads. “With facts, the court can visualize what happened. Facts ‘paint the picture.'”

One sample quiz led by an instructor in FLETC’s legal division, called “Use of Force Test: Do You Know How You’ll be Judged?” focuses on how a court might view an agent’s remarks. Another quiz, on fugitive operations, asks students which legal standard allows for people to sue ICE for damages over violations of the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable search and seizure. The transcript of a training lesson on officer liability outlines legal paths people can pursue to sue law-enforcement agents for misuse of power, wrongful use of force, or other forms of misconduct. “We’ll distinguish the different types of lawsuits, or civil actions, a law-enforcement officer could face,” a senior legal instructor says, “and we’ll also discuss how to get out from under those lawsuits.”

“They’re being taught what words to say to get around the letter of the law or circumvent the spirit of the law,” Trainum said. “I’m setting up the stage to tell a court I did what I had to.”

On a December 2018 podcast called “Careers at ICE,” produced by the agency for people interested in becoming an immigration officer, features a deportation officer named Christian Rodriguez. “Ninety percent of our job is being able to articulate the reasons as to why we do what we do,” he says. “If I train anybody, I say, ‘Chances are you’re not going to get in trouble for what you do out in the field. You will get in trouble for your inability to articulate why you did what you did.'”

A scenario-based lesson called Team Tactics, dated 2007, guides agents on how to operate around the constraints of administrative warrants. In it, instructors teach ICE trainees how to extract consent to enter private property.

“Stress verbal techniques that may be employed to coax the target out of the residence,” the notes read. When hoping to enter a place of business, they say, “Students should apply verbal techniques, with the intent of having the manager grant consent.”

The lesson includes discussion of how a “hot-pursuit scenario” may allow officers to engage in a warrantless search or arrest. “Stress the factors the court will consider in determining exigency to justify a warrant less search,” the instructor notes read.

Including Causey, we identified seven ICE officers or agents named as defendants in lawsuits alleging misconduct over their use of firearms. One case was settled without admission of wrongdoing. Another case is still underway.

Every other suit was dismissed.