Europe’s largest renewable power producer is scaling back plans to build new wind and solar plants because of lower electricity prices and higher costs.

Statkraft chief executive Birgitte Vartdal, who took over in April, has pledged to “sharpen” strategy to cope in a tougher environment.

“The transition from fossil to renewable energy is happening at an increasing pace in Europe and the rest of the world. However, the market conditions for the entire renewable energy industry have become more challenging,” she said.

Although Statkraft is not listed, public markets have highlighted the falling demand for renewables.

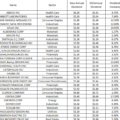

The S&P Global Clean Energy Index, which includes wind turbine and solar-panel makers, has dropped 25 per cent since July last year, while ESG equity funds have suffered $38bn in outflows this year to the end of May, says Barclays.

Statkraft, which is owned by the Norwegian state and mostly produces energy from its vast fleet of hydropower stations, announced plans to slow capacity growth on Thursday

It now aims to install 2-2.5GW of onshore wind, solar and battery storage annually from 2026 onwards — potentially enough to supply electricity to about 2.5mn households. That compares with a previous target of 2.5-3GW annually from 2025 and 4GW annually from 2030.

For offshore wind, it now aims to develop 6-8GW in total by 2040, down from its previous target of 10GW.

“We still believe strongly in offshore wind and would like to stay in there, but we are reducing our ambition somewhat,” Vartdal said. Last year it bought Spanish renewable energy company Enerfin for €1.8bn.

Statkraft is among several European utilities to slow growth plans over the past year.

Denmark’s Ørsted, the world’s largest offshore wind developer, slashed its targets for 2030 by more than 10GW after running into difficulties on US projects.

Meanwhile, Portugal’s EDP also cut its annual targets in May, blaming “lower electricity prices and a higher interest rate environment for longer”, chief executive Miguel Stilwell d’Andrade said at the time.

The moves come despite the growing political push on renewables, with countries agreeing at the COP28 climate summit last November to try and triple global renewables capacity by 2030.

“Projects have become much more challenging and relative returns simply aren’t there,” said Vegard Wiik Vollset, vice-president, and head of renewables and power at Rystad Energy, a consultancy.

“I would argue that this is not great for the energy transition. Its relative speed is put into question.”

On hydrogen, Statkraft has cut its target of 2GW by 2030 to 1-2GW by 2035.

The fuel is seen by many governments as critical to decarbonisation targets, but requires government support to jump-start supply chains and demand.

Engie, the French state-backed utility, pushed back its target to develop 4GW of hydrogen projects from 2030 to 2035, arguing that the “development and structuring [of the market] is slower than was envisaged a year ago”.