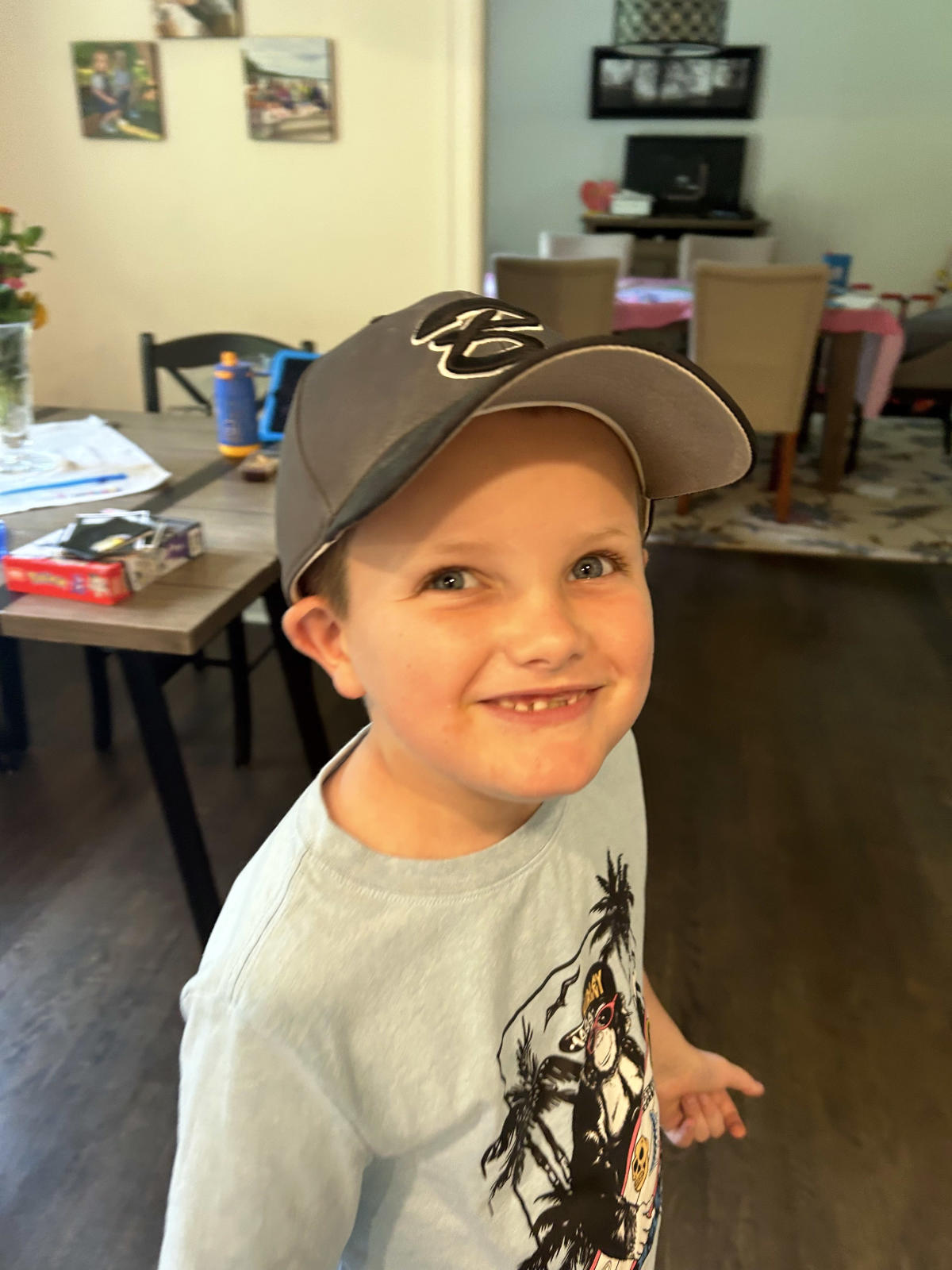

During the COVID-19 lockdown, Courtney bought a bounce house for her two young children. Soon after, her son, Alex, then 4, began experiencing pain.

“(Our nanny) started telling me, ‘I have to give him Motrin every day, or he has these gigantic meltdowns,’” Courtney, who asked not to use her last name to protect her family’s privacy, tells TODAY.com. “If he had Motrin, he was totally fine.”

Then Alex began chewing things, so Courtney took him to the dentist. What followed was a three-year search for the cause of Alex’s increasing pain and eventually other symptoms.

The beginning of the end of the journey came earlier this year, when Courtney finally got some answers from an unlikely source, ChatGPT. The frustrated mom made an account and shared with the artificial intelligence platform everything she knew about her son’s symptoms and all the information she could gather from his MRIs.

“We saw so many doctors. We ended up in the ER at one point. I kept pushing,” she says. “I really spent the night on the (computer) … going through all these things.”

So, when ChatGPT suggested a diagnosis of tethered cord syndrome, “it made a lot of sense,” she recalls.

Pain, grinding teeth, dragging leg

When Alex began chewing on things, his parents wondered if his molars were coming in and causing pain. As it continued, they thought he had a cavity.

“Our sweet personality — for the most part — (child) is dissolving into this tantrum-ing crazy person that didn’t exist the rest of the time,” Courtney recalls.

The dentist “ruled everything out” but thought maybe Alex was grinding his teeth and believed an orthodontist specializing in airway obstruction could help. Airway obstructions impact a child’s sleep and could explain why he seemed so exhausted and moody, the dentist thought. The orthodontist found that Alex’s palate was too small for his mouth and teeth, which made it tougher for him to breathe at night. She placed an expander in Alex’s palate, and it seemed like things were improving.

“Everything was better for a little bit,” Courtney says. “We thought we were in the home stretch.”

But then she noticed Alex had stopped growing taller, so they visited the pediatrician, who thought the pandemic was negatively affecting his development. Courtney didn’t agree, but she still brought her son back in early 2021 for a checkup.

“He’d grown a little bit,” she says.

The pediatrician then referred Alex to physical therapy because he seemed to have some imbalances between his left and right sides.

“He would lead with his right foot and just bring his left foot along for the ride,” Courtney says.

But before starting physical therapy, Alex had already been experiencing severe headaches that were only getting worse. He visited a neurologist, who said Alex had migraines. The boy also struggled with exhaustion, so he was taken to an ear, nose and throat doctor to see if he was having sleep problems due to his sinus cavities or airway.

No matter how many doctors the family saw, the specialists would only address their individual areas of expertise, Courtney says.

“Nobody’s willing to solve for the greater problem,” she adds. “Nobody will even give you a clue about what the diagnosis could be.”

Next, a physical therapist thought that Alex could have something called Chiari malformation, a congenital condition that causes abnormalities in the brain where the skull meets the spine, according to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Courtney began researching it, and they visited more doctors — a new pediatrician, a pediatric internist, an adult internist and a musculoskeletal doctor — but again reached a dead end.

In total, they visited 17 different doctors over three years. But Alex still had no diagnosis that explained all his symptoms. An exhausted and frustrated Courtney signed up for ChatGPT and began entering his medical information, hoping to find a diagnosis.

“I went line by line of everything that was in his (MRI notes) and plugged it into ChatGPT,” she says. “I put the note in there about … how he wouldn’t sit crisscross applesauce. To me, that was a huge trigger (that) a structural thing could be wrong.”

She eventually found tethered cord syndrome and joined a Facebook group for families of children with it. Their stories sounded like Alex’s. She scheduled an appointment with a new neurosurgeon and told her she suspected Alex had tethered cord syndrome. The doctor looked at his MRI images and knew exactly what was wrong with Alex.

“She said point blank, ‘Here’s occulta spina bifida, and here’s where the spine is tethered,” Courtney says.

Tethered cord syndrome occurs when the tissue in the spinal cord forms attachments that limit movement of the spinal cord, causing it to stretch abnormally, according to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons. The condition is closely associated with spina bifida, a birth defect where part of the spinal cord doesn’t develop fully and some of the spinal cord and nerves are exposed.

With tethered cord syndrome, “the spinal cord is stuck to something. It could be a tumor in the spinal canal. It could be a bump on a spike of bones. It could just be too much fat at the end of the spinal cord,” Dr. Holly Gilmer, a pediatric neurosurgeon at the Michigan Head & Spine Institute, who treated Alex, tells TODAY.com. “The abnormality can’t elongate … and it pulls.”

In many children with spina bifida, there’s a visible opening in the child’s back. But the type Alex had is closed and considered “hidden,” also known as spina bifida occulta, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“My son doesn’t have a hole. There’s almost what looks like a birthmark on the top of his buttocks, but nobody saw it,” Courtney says. “He has a crooked belly button.”

Gilmer says doctors often find these conditions soon after birth, but in some cases, the marks — such as a dimple, a red spot or a tuft of hair — that indicate spina bifida occulta can be missed. Then doctors rely on symptoms to make the diagnosis, which can include dragging a leg, pain, loss of bladder control, constipation, scoliosis, foot or leg abnormalities and a delay in hitting milestones, such as sitting up and walking.

“In young children, it can be difficult to diagnose because they can’t speak,” Gilmer says, adding that many parents and children don’t realize that their symptoms indicate a problem. “If this is how they have always been, they think that’s normal.”

When Courtney finally had a diagnosis for Alex, she experienced “every emotion in the book, relief, validated, excitement for his future.”

ChatGPT and medicine

ChatGPT is a type of artificial intelligence program that responds based on input that a person enters into it, but it can’t have a conversation or provide answers in the way that many people might expect.

That’s because ChatGPT works by “predicting the next word” in a sentence or series of words based on existing text data on the internet, Andrew Beam, Ph.D., assistant professor of epidemiology at Harvard who studies machine learning models and medicine, tells TODAY.com. “Anytime you ask a question of ChatGPT, it’s recalling from memory things it has read before and trying to predict the piece of text.”

When using ChatGPT to make a diagnosis, a person might tell the program, “I have fever, chills and body aches,” and it fills in “influenza” as a possible diagnosis, Beam explains.

“It’s going to do its best to give you a piece of text that looks like a … passage that it’s read,” he adds.

There are both free and paid versions of ChatGPT, and the latter works much better than the free version, Beam says. But both seem to work better than the average symptom checker or Google as a diagnostic tool. “It’s a super high-powered medical search engine,” Beam says.

It can be especially beneficial for patients with complicated conditions who are struggling to get a diagnosis, Beam says.

These patients are “groping for information,” he adds. “I do think ChatGPT can be a good partner in that diagnostic odyssey. It has read literally the entire internet. It may not have the same blind spots as the human physician has.”

But it’s not likely to replace a clinician’s expertise anytime soon, he says. For example, ChatGPT fabricates information sometimes when it can’t find the answer. Say you ask it for studies about influenza. The tool might respond with several titles that sound real, and the authors it lists may have even written about flu before — but the papers may not actually exist.

This phenomenon is called “hallucination,” and “that gets really problematic when we start talking about medical applications because you don’t want it to just make things up,” Beam says.

Dr. Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, president of leading U.S. physicians’ group the American Medical Association, tells TODAY.com in a statement that the AMA “supports deployment of high-quality, clinically validated AI that is deployed in a responsible, ethical, and transparent manner with patient safety being the first and foremost concern. While AI products show tremendous promise in helping alleviate physician administrative burdens and may ultimately be successfully utilized in direct patient care, OpenAI’s ChatGPT and other generative AI products currently have known issues and are not error free.”

He adds that “the current limitations create potential risks for physicians and patients and should be utilized with appropriate caution at this time. AI-generated fabrications, errors, or inaccuracies can harm patients, and physicians need to be acutely aware of these risks and added liability before they rely on unregulated machine-learning algorithms and tools.”

“Just as we demand proof that new medicines and biologics are safe and effective, so must we insist on clinical evidence of the safety and efficacy of new AI-enabled healthcare applications,” Ehrenfeld concludes.

Diagnosis and treatment

Alex is “happy go lucky” and loves playing with other children. He played baseball last year, but he quit because he was injured. Also, he had to give up hockey because wearing ice skates hurts his back and knees. He found a way to adapt, though.

“He’s so freaking intelligent,” Courtney says. “He’ll climb up on a structure, stand on a chair, and starts being the coach. So, he keeps himself in the game.”

After receiving the diagnosis, Alex underwent surgery to fix his tethered cord syndrome a few weeks ago and is still recovering.

“We detach the cord from where it is stuck at the bottom of the tailbone essentially,” Gilmer says. “That releases the tension.”

Courtney shared their story to help others facing similar struggles.

“There’s nobody that connects the dots for you,” she says. “You have to be your kid’s advocate.”

This story was updated to include a statement from the American Medical Association.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com