THE PARADOXES of Brexit multiply by the day. Brexit was supposed to allow Britain to take back control of its destiny. This week a British prime minister sat in a windowless room in Brussels while 27 European countries debated the country’s future in the council chamber (though Donald Tusk, the European Council’s president, did nip out halfway through the meeting to keep her updated). Brexit was supposed to restore the sovereignty of parliament. This week a British prime minister, borrowing the language of demagogues down the ages, berated MPs for not enacting the “will of the people”. Brexit was supposed to force the political class to venture out of its bubble and rediscover the rest of the country. The political class—journalists as well as politicians—is more navel-gazing than ever. I could go on but I think you get the general drift….

****

IN THE Blair-Cameron years politicians competed to be as bland as possible. Today they compete to be as grotesque as possible. The age of identikit politicians (which culminated in the Jedward that was Cameron-Clegg) has been replaced by the age of caricatures.

Jeremy Corbyn is one of George Orwell’s sandal-wearing pacifists drunk on his own moral purity. His office is full of upper-class socialists who fell in love with the working-class while attending some of the world’s most expensive schools. Theresa May is an archetypical grammar-school girl who thinks that she’ll get a gold star if she keeps re-writing the same essay in neater handwriting. John Bercow, the Speaker of the House of Commons, is a classic puffed-up little man who likes to remind MPs of the importance of brevity in labyrinthine sentences that include, in no particular order, words like “sedentary”, “chuntering” and “loquaciousness”. The hard-core Brexiteers are divided into two types: golf-club bores who could sort it all out if they were put in charge and mumbling monomaniacs who keep dragging the conversation around to the same point.

****

THE CARICATURES on both the left and the right have one powerful argument on their side: that they represent “real Labour” or “real Conservatism”. The left’s trump card has always been that “real” Labour voters are coal-miners and steel-workers—and that “real” Labour policies have always been about redistributing income and nationalising things. The right can’t summon up a “real” Tory voter in quite the same way—the Party survived its aristocratic past by discovering “real Tories” in every social class—but it has made up for this by emphasising “real Tory” values: flag-waving nationalism, suspicion of foreigners, belief in British exceptionalism.

More moderate elements in each party have always been haunted by the fear that they are betraying the real party. Tony Blair had to resort to a combination of top-down control (policing not just what MPs said, but also what they wore) and cynical gesture politics (the hunting ban). Theresa May has repeatedly given in to the Brexiteers despite her realisation, as a rising politician, that a Tory party keen to recruit new members needed to shed its image as “the nasty party”, rather than becoming a rest home for elderly cranks.

****

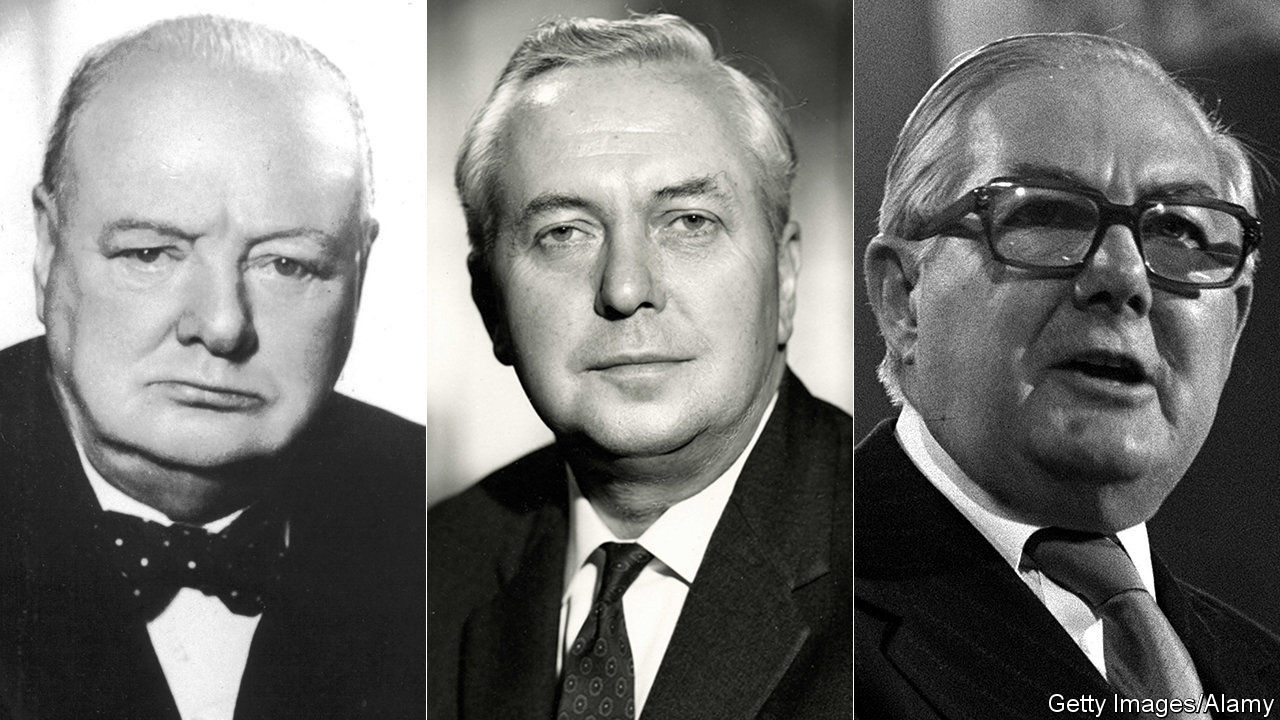

THIS WEEK provided yet further proof—as if we needed any—that the country’s political class is in dismal shape. Britain not only has the worst prime minister and the worst leader of the opposition it has ever had. It has the worst cabinet and shadow cabinet as well. For much of the democratic era Britain contrived to send the most talented members of its various sub-divisions into parliament: Winston Churchill (pictured left) from the landed elite; Harold Wilson (pictured centre), Richard Crossman, Anthony Crosland from the intellectual elite; Ernest Bevin, Nye Bevan, Jim Callaghan (pictured right) from the working classes. Now it not only sends less talent but leaves much of the talent that it does send stuck on the back benches.

That said, I’m sceptical of the idea popular in business circles that all the great talent has migrated to the business sector and all we need to do is to recruit a few more business types and Britain will be on the road to recovery. I’m struck by how many business types are essentially private-sector bureaucrats who spend their (very well-paid) time holding meetings and recycling memos. Certainly, the performance of those business types, such as Archie Norman, who have gone into politics is far from inspiring.

I think there is a deeper problem with the nature of Britain’s governing class as a whole: a problem more to do with the corruption of its soul than with the allocation of talent between various sectors. The governing class has lost its sense of public service and become obsessed with lining its own pockets. Not that long ago retiring politicians spent their retirements cultivating their gardens and giving sage advice in the House of Lords. Now they join the ranks of the super-rich, not just stuffing their pockets with gold, which I can understand, but also devoting their spare time socialising with billionaires, playboys and dynasts, which I find incomprehensible. A good part of the appeal of Jeremy Corbyn is that, for all his failures of intellect and judgment, he is at least a self-denying type who lives an austere life.

The loss of a sense of public service is also driven by two more profound structural changes. The first is the advance of the division of labour. Academics write for other academics. Business people are overwhelmed by an ever-multiplying list of metrics (many of them imposed by the government). The second is a profound loss of cultural self-confidence. For all the differences between Tories and Labour the governing class used to share a common sense of cultural values: they might disagree about who got what but they agreed about the virtues of Western (and particularly English) civilisation. Now that those common cultural values have been dissolved by the acids of academic fashion and interest-group politics it is much easier to abandon public life entirely and concentrate on making money.