As part of its “Portfolio Basics” series, Morningstar has an educational article on taxable bonds, including corporate bonds, US government bonds, and foreign government bonds, along with their different credit grades and maturity lengths.

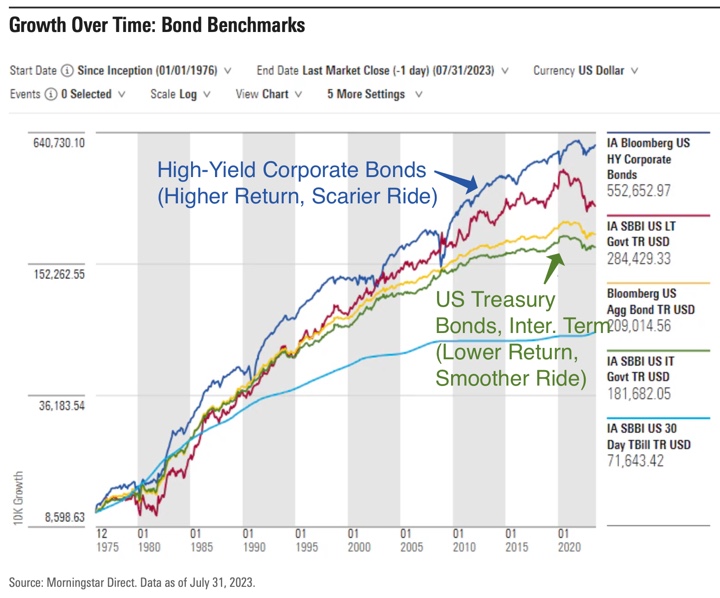

Over the last 20 years, things have played out pretty much as the traditional theory would have predicted. The higher the “risk”, the higher the return. High-yield “junk”-rated corporate bonds have had the highest return, but also the bumpiest ride due to their higher credit risk and higher interest rate risk (they are usually of longer maturity). Short-term US Treasury bills (“cash”) has had the lowest return but the lowest credit risk and lowest interest rate risk. Personally, I see this chart and am satisfied with my holdings of intermediate-term US Treasury bonds (green line) that keeps the highest credit risk but with effectively a ladder out to a longer average maturity.

But hey, those high-yield bonds still returned a lot more money over the last 20 years instead. Why not just hold those instead? First, don’t forget to step back and look at the bigger picture:

If you’re going to accept big swings, you might prefer one of the highest returning assets in the top-right corner. (I have no idea which one will be the absolute highest in the next 20 years, but I don’t think it’s an accident that all the stocks are grouped together in that top-right corner.) If you can hold on through the scary periods, the gap between stocks and bonds over the long run (~100 years below) is huge:

This is why many will advise you to own more stocks if you want an overall higher risk/potentially higher return profile, as opposed to riskier bonds. But before you get carried away, read this book excerpt Courage Required from William Bernstein. Bleak times will come again. Safe things have value beyond the rate of return.