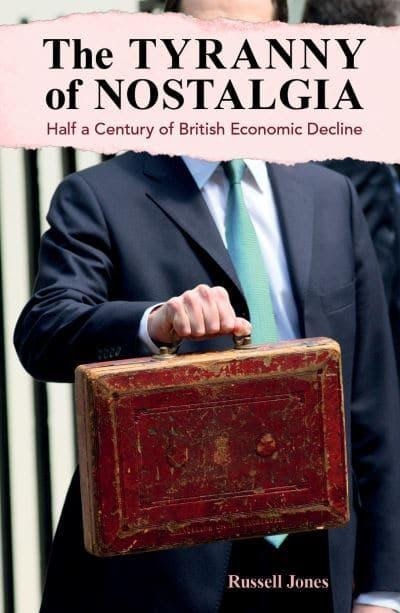

Russell Jones has

written a history of the UK economy since the 1970s, and

as narratives go this is very good. While I inevitably had minor

points of disagreement, on most issues I think the author makes the

right calls. The narrative is clear and not unnecessarily technical,

so you don’t need to be an economist to read it. (The book is also

chart free, which I think is a shame.) It is very

comprehensive implying extensive research, which is quite an achievement when writing about 50

years of economic developments and policies.

These virtues have

costs, of course, at least for an academic like me. Being

comprehensive can mean that you give too many reasons why this or

that happened, or particular policies failed, rather than focusing on

the key drivers. That in turn can lead to ambiguities or

inconsistencies. One rather interesting one is the conflict that

emerged between PM Brown and Chancellor Darling over the relative

priorities to be given to the recovery (requiring fiscal stimulus)

and controlling the growing budget deficit (requiring fiscal

consolidation). While I sense that the author favours Darling on

this, his later discussion on austerity rather suggests that Brown

was right.

As this blog has

featured many of the episodes covered by this book, I will not try to

go over this ground again here with a short narrative about a longer

narrative. (For this, see William Keegan’s nice

review). Instead let me try and do something

different. I want to use the book as material to bust several widely

held myths about the macroeconomic history of the UK over the last

fifty years.

-

There is no

relentless decline. This is a point I have made before but cannot be repeated too often, given the UK economic

declinism temptation many fall into. This period

might have started and ended in relative decline compared to the US,

Germany and France, but from the 1980s until around the Global

Financial Crisis the UK economy grew as fast or faster than these

economies. This is a point the author notes at various places in the

text, although the book’s title and conclusions do relapse

somewhat. .

It is this relative performance that really matters. Those who say

Thatcherism and New Labour disappointed because growth was no better

or maybe even worse than in the golden age after WWII ignore that

starting point! The reality is that much of Europe and Japan were

rebuilding their economies after large scale destruction during the

war, and the UK was bound to see some of the benefit of that. The UK

economy may have never had it so good in the 1950s, but it was

falling behind other major economies, which is one of the reasons we

kept trying, and eventually succeeded, in joining the EU.

-

The relative

unimportance of economic thought. The myth that it is otherwise is

often promulgated by economists, suggesting that economic history is

to a considerable extent determined by changing economic ideas

within academia. So, for example, the story goes that In the UK

Keynes ruled from WWII, but Keynesianism failed in the 1970s with

high inflation, so Freidman and monetarism took over from the 1980s.

While the author does describe changing academic fashions at various

points in the book, reading his account confirmed my view that these

changing academic winds were generally not the key driver of policy

changes.

In my view the key policy failure of the 1960s and 1970s was that

policymakers were determined to avoid using demand management as a

means of moderating inflation. It is not, as James Forder has

pointed out, that policy makers were using the wrong

Phillips curve, but just that UK policymakers didn’t want to use

the Phillips curve at all. To call this reluctance ‘Keynesian’ is

really too far a stretch, as neither Keynes nor those who developed

Keynesian theory were great proponents of prices and incomes

policies.

Equally, in the narrow sense of the term, what came after the

1970s was not monetarism. As the book makes clear, money supply

targets were briefly tried and failed miserably, with great harm done

to UK manufacturing and many who worked in it. What changed in 1979

was the UK got a Prime Minister and Chancellor who were no longer

committed to maintaining full employment, but were determined to get

inflation down without resorting to prices and incomes policies.

Today the reluctance of policymakers in the 1960s and 1970s to use

the Phillips curve to control inflation looks like a temporary

aberration reflecting a determination not to repeat the disaster of

the Great Depression. [1]

Equally the idea that austerity was the result of work by

Alesina or Reinhart and Rogoff is nonsense. The unfortunate truth is

that there will always be some economists around to give even the

craziest policies some respectability, as Brexit showed. The pandemic

taught us that this is not a peculiarity of economics, but can happen

with supposedly harder sciences as well. (Actually, as my

own book argued, medicine is perhaps the closest

discipline to economics.)

If there is an exception to this argument that economic ideas

matter very little to recent UK economic history, I think you can

find that too in this fifty year period. The idea that macroeconomic

stabilisation should come from independent central banks pursuing

inflation targets did come in large part from current academic

economics, rather than politics or Keynes’s 30 year old academic

scribblers.

-

Another

favourite myth of mine that I have talked about before, but which is

clearly shown to be a myth by this book, is that Conservative

politicians are better at managing the economy than Labour

politicians. Labour tends to get the blame for the IMF crisis in the

mid-70s, but this had a lot to do with the earlier Barber boom,

where the author reminds us that policy aimed for 5% growth. The

Thatcher period may have seen relatively good growth on average, but

it was a really bumpy ride because of what can best be described as

destabilisation policy: monetarism, the 1981 budget (Jones describes

this as “an admission of failure”) followed by the Lawson boom,

then ERM membership at an overvalued rate leading to Black

Wednesday. The author is right that Labour inherited a reasonably

healthy economy, but the 1997-2007 period was incredibly stable

compared to the 1980s and early 1990s, in part because macro policy

was much better. Unfortunately 2010 to today has seen a return to

destabilisation policy, first with austerity, then Brexit, then the

government’s reaction to Covid and finally Liz Truss. -

2010 sea

change. 1979 rightly represents an important shift in how UK

economic policy was done, although I would argue this is not so much

from Keynesian to monetarism (see 2 above) as the advent of

neoliberalsm. However 2010 (to 2024?) may also come to be seen as a

similar sea change.From reading this book it is clear that from WWII until 2010

policymakers were constantly looking forward, trying (and sometimes

failing) to deal with real and serious economic problems.

Policymakers constantly worried about the productivity gap (and

therefore prosperity gap) between the UK and Germany, France or the

US, and tried to do something about it. It is a major reason why UK

policymakers wanted to be part of the EU, and then the Single Market.In contrast since 2010 Prime Ministers and Chancellors have

based policy on largely imaginary problems, like austerity or

sovereignty, to further either minority or individual goals. Since

2010 policymakers have stopped focusing on the UK’s relative

productivity compared to Germany, France and the US, and instead have

preferred to tell us that everything they do is ‘world beating’.

It is the shift in focus that is perhaps the underlying story behind

the UK’s relative

decline since 2010.

If you want a

comprehensive and well researched book on which to compose your own

ideas (or bust myths) about UK economic policy over the last 50

years, this book is for you. Alternatively if the subject just

interests you, and you want a well written account that avoids dogma,

I can recommend this book. One thing you can say unequivocally about

UK economic policy over the last half decade is that it has been far

from uneventful or boring.

[1] Just to preempt

the inevitable responses, although basic MMT does hark back to

post-war policies it does also use demand management and the Phillips

curve to control inflation. With a job guarantee what changes is the

number of people on the JG scheme, rather than unemployment.